6.1. We Kill The Sacred Cow* Tonight, So Stick Around (*neoliberal Capitalism)

The Director and George had now drawn out their late-night meal for as long as they possibly could, and as they worked their way through the cheese board, dessert wine and brandy to finish off, that initial amuse-bouche they’d wolfed down an hour-and-a-half before, seemed a long time and many, many calories ago. They were the last guests in the restaurant by some margin, and the maître’d, the waiters and even the chef had gathered in the corner, waiting for their celebrity guests to leave.

“I think we may have overstayed our welcome,” whispered the Director, motioning to the staff. “I’ve said enough anyway.”

This didn’t help George. He’d invested a lot of brain cells in this conversation, had heard about the flaws of a Capitalist system, and now he needed some practical guidance about what to do about it.

“You can’t leave me hanging!” He said urgently. He felt tired and woozy, but he still wanted to know how the final piece of this jigsaw would fit.

“I get it; we need a new approach, but what? This happens all the time. People say we’ve got to do something, but they never explain what that something is. So are you going to let me down as well?”

The Director was impressed by George’s sincere persistence.

“Tell you what,” he said, “why don’t we retire to the bar for a nightcap, I can go over a few of my ideas and then, if I’ve answered your questions, I can order a cab and get home to my poor wife.”

“Sounds good!” said George, removing his napkin and helping the Director to his feet. They then moved into the bar and climbed onto the barstools. Once settled, the Director began his homily again:

“George, we’ve talked about how Capitalism isn’t what it seems, but also that it isn’t a grand conspiracy created by an elite group of puppet masters. Sure, the GRiFTers have been riding that gravy train for the last two hundred and fifty years, but you can’t blame them for that.”

“I guess a GRiFTer’s gonna do what a GRiFTer’s gonna do.” Said George philosophically.

“You’re right, but we can only move on if we accept that most of us would do exactly the same if we were in their shoes.”

This was a challenging idea, but George continued to listen, knowing there was a grain of truth in this, even if he didn’t want to admit it.

“Tolstoy said Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself. It’s hard to admit, but we’re all playing the Capitalist game, and we won’t fix anything until we are willing to admit it. And that’s the point I was trying to make in the film.” Concluded the Director. “We can end this crisis right now if we all just stopped being so bloody selfish. It really is that simple!”

“Harsh, but I guess the truth hurts.” Said George.

“Don’t get me wrong; I’m not blaming anyone.” Replied the Director, matter-of-factly. “But we need a sort of Truth and Reconciliation session before we can start to work together and put things right. That big bad Dragon can only survive if we feed it, and we do that through feeding our own greed and selfishness. But if we stop feeding the little dragon inside ourselves, the big Dragon will leave us alone, too.”

“I’ve got a little dragon inside me?” asked the bartender genially, overhearing her new guests’ animated discussion.

“You’d better believe it.” Confirmed George excitedly. “Just like the one in Alien, and if we don’t kill it quickly, it’s going to destroy the whole ship, and we’re all going to die! Except maybe Sigourney Weaver and the cat.”

“Really?” Blurted the bartender in surprised amusement.

“I’m afraid so, and because we don’t like to own up to our greed, we blame the big bad Dragon instead.” Continued George.

The Director was increasingly concerned by George’s interpretation of what he’d tried to convey over the past six hours and feared this disturbing version of the story might be off-putting to the uninitiated. So he took back the initiative and tried to steer the conversation away from lizards bursting out of chest cavities. “Maybe think of it more as Willy Wonka,” said the Director, looking for a friendlier movie reference. “What would the world look like if we all stopped being greedy, selfish Augustus Gloopsand started being kind and considerate Charlie Buckets? If we did that, we’d change the world.”

‘Wow…’ said the bartender quietly to herself, wondering what the hell she’d walked into. Meanwhile, as she waited for an appropriate moment to take their order, she recognised these two gentlemen as being that somewhat schlocky Hollywood actor and that elder statesman of the British film industry. Still, she’d served a lot of famous faces in this bar, so she wasn’t about to be stage-struck. In any case, they both looked like they’d already had quite a lot to drink, to say the least.

“But, of course, it isn’t that easy.” Continued the Director, adding a hint of caution to his analogy. “If it was, we’d have slain this Dragon years ago.”

‘OK, we’re back to dragons again,’ thought the bartender, but she didn’t interrupt. After all, the client was always right, right? And she was confident enough to know she’d pick up the conversation once she’d a few more clues about what they were talking about.

“What’s been missing is a willingness to walk away from a system that’s been working pretty well for us.” Explained the Director, addressing the young bartender directly. “I mean, so long as you’re a white, middle-class man born in a developed country, why rock the boat?”

The bartender offered a face that said, I hear you.

“Of course, there aren’t many of us left who think Capitalism is perfect. I mean, anyone with a conscience might feel a tad guilty for the way we exploit poorer nations, but hey, out of sight, out of mind, eh?” To which he added a nonchalant shrug.

The bartender looked at George to see if he agreed. George nodded back an affirmative, so the bartender nodded, too.

“And to salve our conscience, the GRiFTers are always on hand to remind us there’s no alternative,” continued the Director, assuming this would make perfect sense to a total stranger. “So why waste our time looking behind the curtain?”

“Why indeed?” Agreed the bartender, wondering what a GRiFTer might be. She’d also seen her chance to ask, “So, what can I get you gentlemen, on this damp autumn evening?”

“Well, I’ll have a large 12-year-old Glenlivet, please, and my friend here will have a… ?”

“… Jack and Coke, please”, said George, predictably.

The Director looked to George to see if he might make a ‘pass’ at the bartender. He liked to use this little test to evaluate his leading men: Would George use his fame and wealth to take advantage of the women he met?

George’s blank expression suggested his mind was elsewhere. From the look on his face, he was still grappling with fundamental issues related to social economics: George was no sleazeball, which very much endeared him to the Director.

The bartender smiled and moved away to attend to her other guests and, in this lull in proceeding, the Director contemplated George’s rather bland profile. The actor looked a little shell-shocked as he attempted to skewer the last olive from the complimentary bowl in front of him. Perhaps this guileless but affable actor had finally been inundated by the unrelenting torrent of information he’d been subjected to for the past 6 hours. Or maybe he just really felt like eating that last olive. The Director was unsure, but he did know there were still a few more essential plot points to get across before he could let George turn in for the night.

For a start, there was the little matter of explaining why it was far easier to tempt humans to be selfish than encourage them to be generous. And, of course, he still had to offer an alternative, sustainable vision for humanity. So, the Director mentally planned a route for delivering his message in what was left of the evening.

6.2. Everybody Wants To Rule The World

“George, do you remember how we discussed Monopoly earlier when I explained the concept of Rent Extraction?”

“I do.” Confirmed George, feeling they’d talked about it a lifetime ago.

“But I didn’t ask whether you actually liked playing it?”

“I do, very much.” Replied George, reminiscing. “Back home, we all get together at Christmas and play it as a sort of tradition. Takes us about three days to finish a game.… Why do you ask?”

“Well, you might not know this, but there was an earlier version of Monopoly called The Landlord’s Game?

“I did not know that,” replied George, his curiosity piqued.

“It was designed by an American called Lizzie Magie around 1900. She was something of a socialist and created the game to demonstrate the evils of actual monopolies in the real world. She devised two ways of playing. The first was the Monopoly version, like the game we play today, where the objective is to bankrupt your opponents. The other was called Prosperity, where you worked with the other players to make sure everyone won.

“It became a craze among Harvard students and the Quaker community, but the interesting thing is that the Monopoly version was far more popular. Nowadays, no one remembers Prosperity. It’s as if it never existed. And, it’s my guess that’s because it’s much more fun grinding your opponents into the dust than giving them a helping hand.”

“Interesting, but what’s your point?” asked George.

“My point is that we’re more easily seduced by selfishness than by cooperation.

“Another good example of the greedy dragon inside us”, continued the Director, “is a parable called The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits, written by a Dutchman called Bernard Mandeville who was living in London around 1705. The central idea of his book was that while private vices might be morally questionable, they inadvertently built a better, more prosperous society, which is a concept that predated Adam Smith’s book by 50 years. Even so, the London elite wasn’t ready for this level of honesty and didn’t much care to be told they were greedy, promiscuous and vain!”

“So what’s new?” asked George acerbically. “This Mandible guy was only telling them that Greed is Good, which iswhat Gordon Gekko was shouting about in Wall Street.”

“Fifty years later, Adam Smith said more or less the same thing in the Wealth of Nations, but he wrapped his ideas up in academic respectability, so those same greedy capitalists lapped it up!

“He was pushing against an open door,” said George.

“He was,” agreed the Director. “He gave the Establishment a fig leaf to hide behind, forgiving them their greed because it was somehow, miraculously, helping the poor get richer too! He let them have their cake and eat it.”

“And they’ve been stuffing their pie-holes ever since.” Exclaimed George with delight.

Both were now drowsy, thanks to the sugar rush brought on by their excessive dessert consumption.

“That’s right, and the point I’m making is that while we all have a latent streak of selfishness in us, especially when we’re encouraged to be selfish by our culture, it doesn’t mean we’re obliged to be selfish. Adam Smith claimed that greed was a law of nature, but that’s rubbish; it’s a choice we make.”

“Here you go gentlemen: One large Glenlivet and one Jack and Coke.” Said the bartender, returning with their drinks.

Without trying to make it look obvious, she took her time laying out the little paper coasters for their glasses in order to hear more of what the Director had to say.

The Director didn’t mind. He was happy for anyone to listen to his views on this subject. To him, it was a matter of life and death.

“I am trying to remember if I’ve told you this already, George, but it’s my theory that Adam Smith wasn’t necessarily right. He was just in the right place at the right time, and things might have been very different if we’d listened to a different Adam.”

George attempted the intrigued face he reserved for that scene in a film where he was told significant information essential to the plot.

“Take Adam Ferguson, for example. Like Adam Smith, he was a good Scotsman, and they were, in fact, close friends. Nine years before Smith published The Wealth of Nations, Ferguson wrote his own book called An Essay on the History of Civil Society, in which he suggested that societies worked better when they were built on cooperation and social bonds. Unlike Smith, he thought a capitalist society made men weak, dishonourable and selfish. But, as we’ve seen already, this point of view was much less likely to make the Capitalist Elite richer and more powerful, so it was largely ignored by the, ahem, Capitalist Elite.”

“Quelle Surprise!” Said George in a sarcastic Californian/French accent.

“But just imagine if Ferguson’s book had been the best-seller and The Wealth of Nations had ended up in theremaindered bin, we might now be living in a very different world.” Speculated the Director a little despondently.

“I guess them’s the breaks.” Observed the bartender, no longer making any effort to disguise her eavesdropping.

“Them’s are, indeed, the breaks”, agreed the Director, smiling and raising his glass to her.

“I get it. So I’m a greedy son-of-a-bitch, and I’m only interested in myself!” said George, responding to the Director’s suggestion that, given half a chance, people are more than happy to be selfish. “And maybe the world would be better if we were all just a bit nicer to each other. But I haven’t done too badly out of the evils of Capitalism. I mean, look at me!” At which point, George spread his arms.

“You make a good point.” Agreed the Director. The bartender nodded too, intrigued to hear the response to this perfectly reasonable challenge.

“This is exactly what we need to explain if we want people to sign up to our project. So I think it’s time I told you how we can change direction.” Concluded the Director rather grandly.

“Hallelujah!” Declared George, throwing both arms in the air.

6.3. Do You Realise…

At this point, the Director, clearly a little drunk, motioned to George and the bartender to lean in closer. “But first, I have a confession to make.”

“What’s that?” asked George, slightly concerned about what was coming.

“I’ve been a very naughty boy, and I’m ashamed of what I’ve done.” Whispered the Director conspiratorially. The bartender braced herself. “I wasn’t always an Oscar-winning director, you know. I used to be in advertising.”

On overhearing what had been said, George let out a relieved chuckle, “Ha! Is that all? You’ve told me this already! I thought you’d been arrested for exposing yourself or something.”

“No, nothing like that, but back in the 80s, I used to film chimpanzees drinking tea. I used to sell cigarettes. I didn’t care. It was good money. Me, Ridley, Parker and Putnam were all at it. Straight out of art college and into Soho, making our little films that sold empty dreams to the eager masses.”

“There’s worse things,” replied the bartender sympathetically. “My parents are just the same. Back in the 70s, no one cared.”

“But I should have cared!” Cried the Director forlornly. “I’d read Small is Beautiful, soI knew I was helping to store up trouble for future generations, but I assumed I’d be dead from the booze or drugs before then. But here I am, still feeling guilty for the part I’ve played in creating this mess. Advertising hacks like me said it was OK to be selfish, but now I realise we were just hideous Sirens, tempting people to buy stuff they didn’t need, and now we’re about to hit the rocks, and we’re all going to drown.”

“Come on,” said George, “you can’t blame yourself. Everyone was doing it back then.”

“But that’s exactly the point: No one was taking responsibility. It was always someone else’s fault and look where that’s got us. And that was a dereliction of duty. So the first thing we’ve got to do now is stop pointing the finger at others and start taking a look at ourselves in the mirror.”

The Director was now looking quite sad as he drained his glass. “Two more of the same, please, barman!” He said, not bothering with the correct pronoun.

“Well, I think you’re being hard on yourself,” said George consolingly, “I remember there was a time I used to love going to Sea World. It was incredible to watch those orcas performing their stupid tricks every day and they seemed to be having a whale of a time, ho ho, so I couldn’t understand how it was cruel. But over the years, as I’ve learned more about it, I’ve changed my mind. Now I think all those dolphin attractions must be closed down. I guess that’s progress.”

“When the facts change, I change my mind.” Said the bartender reflectively. The conversation had been too compelling for her to leave and get their order.

“I’ve been saying that all day, too!” said the Director. “John Maynard Keynes!”

“He’s the man!” Agreed the bartender, finally leaving to get their drinks.

This conversation helped cheer the Director up, and he mentally thanked George for the effort.

“But what happens if we stop buying stuff?” asked George, picking up the Director’s point about advertising. “Won’t society grind to a halt? I mean, if I owned a little hardware store and people stopped buying my hammers and nails, I wouldn’t have an income, so I wouldn’t be able to pay my taxes. Who would build the hospitals and schools then? And don’t tell me we’ll all live in a commune because I’m not wearing hemp. That’s not going to happen.”

“Ah!” replied the Director. “This is what everyone worries about when they get to this point in the conversation because all we’ve known is a capitalist system that we’re told works so fucking well.”

“So, I put it to you again, Sir: What’s the fucking answer?” Said George, becoming a little irritated by the Director’s seeming refusal to answer his question. Noting this, the Director looked into George’s eyes, took a deep breath and said, “Nobody knows for certain, George, but, then again, no one really understands Capitalism either. There isn’t a blueprint; it just evolved. And then, Adam Smith comes along and claims it’s some sort of law of nature. But now, this particular version of Capitalism has mutated into that man-eating plant in The Little Shop of Horrors, and it’s about to eat the whole planet! Frankly, Capitalism is way past its sell-by date, and we need to forget all about it, along with Adam Smith’s half-baked ideas.”

George knew the plant in The Little Shop of Horrors was called Audrey II, but he kept this to himself because he didn’t want to look like a know-it-all. Instead, he just folded his arms, looked unimpressed and waited. He still hadn’t heard the Director describe an alternative system he’d feel comfortable with.

Somewhat flustered, the Director said: “So you really want me to describe the alternative to Capitalism when the greatest minds of our day can’t agree on how Capitalism works? Why do I have to meet a more rigorous standard for my system than the one you apply to yours?

“Because,” replied George testily, “As I’ve said already, from where I’m standing, Capitalism works! What’s more, I don’t have to understand it because we’re sitting at this fancy bar in the Battersea Power Station at 1 in the morning, and it’s a very comfortable life I’m living. We’ve just finished a movie. I’m flying back to LA in the morning, and on Tuesday, I’ll be shooting a spread for Richard Mille. I’ve got three Porsches in my garage, and at the weekend, I might drive one of them up to Big Sur and enjoy a cocktail while watching the sun go down. Capitalism might not be the best way to run the world, but why should I be interested unless you can offer me something better? I’m hardly likely to give all that up for a fast track to Stalinist Russia”.

6.4. Can’t Buy Me Love

“OK,” replied the Director, enjoying this new, feisty version of George, “Let me remind you that this beautiful Capitalism you seem so keen on defending is now killing us. Second, if it makes you feel any better, I’ve been working on a new theory that doesn’t completely trash our current economic system but rather offers a more evolved version of it that I think will create a more sustainable planet.”

This DID sounds like progress to George, so he raised his hand to beckon the Director to say more.

“I haven’t quite worked it all out yet,” qualified the Director.

“Get on with it!” shouted George firmly.

“OK, well, you might not have noticed George, but throughout our conversation today, I haven’t used the term Anti-Capitalism.”

This seemed unlikely, given the relentless diatribe he’d endured that day. Still, George was willing to give the Director the benefit of the doubt if it meant getting some sort of answer this side of Christmas.

“OK, I’m listening,” he said, intrigued. “But this had better be good.”

“Attaboy!” Replied the Director briskly. “The thing I want us to focus on is this idea of ownership because, if you think about it, ownership lies at the heart of Capitalism.”

George shrugged as if to say, OK, no big deal.

“Adam Smith thought that owning stuff was the driver of a successful society because it incentivised people to work harder to earn more money to buy more stuff. And, as we’ve already discussed, this was supposed to make everyone better off.”

“Capitalism in a nutshell!” said George matter-of-factly.

“Karl Marx, on the other hand, had different ideas. He believed that owning stuff — especially stuff like machinery, factories and land, which he called the means of production — corrupted society. He worried that if you measured success by how much stuff you owned, everything else became a secondary consideration — including the welfare of other people.”

“Communism in a nutshell!” repeated George, “So, your point?”

“My point is that they were both missing the real issue. The answer doesn’t lie in owning or not owning stuff, but rather, in something neither of them had considered.”

George conceded this was an intriguing idea, so he bowed his head slightly and said, “Go on…”

“OK, now we’re getting somewhere.” Said the Director, rubbing his hands together. “These days, I don’t think anyone flicks through the Marxist-Leninist brochure and says, Yep, that’s the society for me! We’ve seen how it’s worked out in Russia and China, which have both more or less thrown in the towel to allow private ownership to creep in.”

“OK, but what about Cuba and Vietnam?” Challenged Faye, unwilling to let this sweeping statement pass unopposed.

“Good question,” accepted the Director, happy to have his ideas interrogated. “Cuba has done remarkably well under the circumstances, given that, for the past 60 years, they’ve been systematically undermined by the United States who don’t want them to succeed. Yet their education system is good; almost every Cuban can read and write, and they have universal health care, which is more than you can say for the USA. However, the Cuban government doesn’t allow free elections, so it’s hard to know if its people are delighted or not, and I’m sure US propaganda wouldn’t allow fair elections anyway.”

“And Vietnam?” asked Faye, still gnawing at this bone. “I visited it in my gap year and it was fantastic.”

“OK,” said the Director. “I have to admit this is something I know less about, but as far as I can tell, The Communist Party of Vietnam did a great job in rebuilding their country once the Americans had stopped dropping bombs on them in 1976. But it’s really only communist in name now, as you probably noticed when you visited Faye?” said the Director, taking a crafty peek at her name tag to ensure he’d got her name right.

“And that’s the point; you’d be hard-pressed to find a successful country run along communist lines these days. Eventually, they tend to go one way or the other, turning into soft socialist economies like Vietnam.”

“Or ruthless dictatorships like Russia.” Said George flatly.

“Or full-blown capitalist economies where oligarchs like Bezos and Musk run the show.” Added Faye, not willing to give the GRiFTers an easy ride.

“Accepted.” Said the Director.

“So what’s the answer?” asked George, hoping to skip to the denouement of this mystery.

“Well, after extended reflection on this problematic issue, I’ve come to the following conclusion.”

“Drum roll, please!” Said George, literally drumming on the bar.

“I’m proposing we agree that ownership is not a bad thing in itself because, no matter how much we want to spread the love and be good socialists, we also need our own space and sense of identity… Not to mention that I look terrible in a Mao suit. People come in all shapes and sizes, so if we took away our individuality, we’d take away a big part of our reason for being human in the first place.”

George very much agreed and felt heartened by this sentiment.

“But we also need to be careful because, with just a tiny bit of encouragement, it’s easy to swing too far the other way. Then, we end up with a group of autonomous individuals hell-bent on getting what they want at the expense of other people. In other words, a nasty, greedy society where everyone is out for themselves.”

“Not to mention a climate disaster.” Added Faye.

George conceded this was also true, given what he’d learned over the previous few hours. “So what’s your answer?”

“The answer isn’t about ownership at all!” Declared the Director, “It’s about our relationship to the things we own.”

“I’m not sure I follow,” Said George, his brow furrowed in confusion.

The Director knew he’d finally come to his Big Reveal, so he was slightly apprehensive about going further. He’d never explained these ideas to anyone before, but he also knew it was now or never, so he pressed on.

“If you look up the word Capital in a dictionary, you’ll find it derives from the Latin caput, which means head and, therefore, the thing that controls the rest of the body.”

George nodded. He understood this: So far so good.

“So, in Ancient Rome, the Capo also described the ruling class, which owned most of the country’s assets. Therefore, the stuff owned by the Capo was known as their capital. And so, in a roundabout way, the word capital became a descriptor of wealth and assets; consequently, capitalism came to describe a system that pursued this wealth. And all of this is based on the idea of the head.

“Very interesting.” Said George. “But, as I asked a moment ago, what’s your point?”

“My point is that if we stopped subscribing to a society driven by our heads and instead started working towards one that’s motivated by our hearts, we’d create a different world that offers long-term survival rather than short-term gratification.”

“That is interesting.” Agreed George, trying to get his own caput around this concept.

“So I hope you can see my ideas aren’t really anti-capitalist at all; I don’t think it’s a sin for someone to have more money than someone else or to own more stuff. I’m perfectly OK if you drive a nice car or wear a fancy watch. The problems come with this obsession to own more and more and more. I think it’s high time wecut out buying the crap we don’t need, especially as it’s not going to make us happy anyway; that’s just the hegemony talking.

“We have to get clear that there are really only two reasons we want to own something. One is because the thing we want to own has a genuine, intrinsic value. We can admire it; it will be well designed, made with good quality materials, perform a function and so on. If you’ve ever read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which I don’t suppose you have because you’re not as old as me, you’d know that these things have some sort of intrinsic quality.

The second reason we like to buy things is to show off and feel superior.However, it’s crucial to understand thateven when these things are expensive, they may still have little intrinsic value because we want to own them for the wrong reasons. They represent 90% of the products and services that advertising tempts us to buy. And this is what really drives capitalism — it’s all this stuff we don’t need!

“If we can learn to distinguish between these two categories and only buy those things that have intrinsic value, we’ll soon fix capitalism and the environmental crisis along with it.”

“O-K-.” Said Faye slowly, still trying to figure out whether this idea was impressive or underwhelming. “Can you give me a real-world example?”

“Certainly.” Said the Director. “Take fast fashion, for instance: Why do we buy cheap clothes made in sweatshops: Clothes that end up in landfill within six months? This doesn’t make us happy or help the planet. Wouldn’t it be better to save up and buy things of better quality and made with love? They may cost a little more, but they last much longer, and we get more satisfaction from them. In my view, a good, interesting life is built on quality over quantity, and this principle can be applied to almost every sort of product, service or asset we might want to own. This even applies to the machines, factories and land, which Marx called the means of production. The question to ask yourself is the same – it’s not what you want, but why do you want it?

“I see.” Said Faye, now a little clearer.

“I was thinking of maybe calling this Copitalism.” added the Director, almost shyly.

“Copitalism?” Queried George, wondering if he’d heard correctly.

“Copitalism,” Affirmed the Director. “Because the Latin for the heart is Cop, and if Capitalism suggests a system driven by the head, then Copitalism suggests a system that’s guided by the heart.

Copitalism = Buy Less / Buy Better.”

“Wow!” was all George could think of to say, his fingers flicking open beside each of his temples as if to suggest his mind was blown. “Just like the Little Prince!”

“Pardon?” Asked the Director. He knew the book to which George was referring but had never gotten around to reading it.

“You know: And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye,” Said George, hoping to explain the connection he’d just made.

The Director suddenly noticed how George might be a little like the kind and sensitive Little Prince himself.

6.5 With A Little Help From My Friends

“But isn’t all of this just a little pie in the sky?” asked Faye, failing to prevent her scepticism from breaking up this love-fest. “I mean, what are you going to do, bring in a law that says from now on you’re only allowed to buy things you really love? Who’s to know if you bought something for love as opposed to just showing off?”

“A perfectly reasonable question.” Conceded the Director, not in the least bit alarmed by the over-familiarity of this hotel employee. “So, are you up for hearing my plans to bring Copitalism to life?”

Given how tired he felt, George wasn’t sure what he was up for anymore, but he didn’t feel he could turn down such a polite request, so waved his hand and said, “OK, let’s have it.”

Having got the green light, the Director pressed on. “So, while I’m aware that challenging Adam Smith’s precious ideas might be a little presumptuous, given he was a genius and, let’s face it, I’m just a raddled old adman, so what do I know? I’m calling out his theory: I’m saying he got it wrong!” (At this point, the Director took a careful look at the bartender’s name tag again.) “You see Faye, Smith thought his Invisible Hand somehow proved that society functioned best when everyone behaved selfishly, but I don’t think that’s the case at all. If you ask me, the Invisible Hand is just as well-suited – if not more so – to spreading a positive message. So I’m going to take Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand and use it to shout about Copitalism instead!“

“More an Invisible Megaphone then?” Said George, playfully mocking his mentor.

“If you like.” Replied the Director, a little defensively. “But it’s no less fanciful than the Invisible Hand itself.”

“I’m sorry.” Said George, sensing he’d hurt the Director’s feelings.

“That’s OK,” the Director replied, aware that what he was about to say would require a degree of blind faith. “But, I hope you can see I’m using the same argument proposed in The Wealth of Nations, only with a twist. And if my theory is right, Copitalism, or something like it, will be adopted by a more enlightened generation than the last one because, as per the law of the Invisible Hand, it will suit them to do so.”

“Interesting,” said Faye, now swirling an ice cube around in a tumbler.

Encouraged by the fact his audience hadn’t burst out laughing at this idea, the Director continued his thesis with renewed gusto. “You see, as I explained to George earlier today while we were walking back from the studio, while Smith was proposing an Invisible Hand working behind the scenes to create wealth for everyone, he couldn’t explain why it did this. Which was a little embarrassing, given he was part of the Enlightenment boy bandI told George about before, which includedVoltaire, Kant and Isaac Newton. Those guys were part of the Age of Reason, so they liked to base their theories on the Scientific Method, which was certainly an upgrade on superstition and religious dogma, which had been how things got approved during the Middle Ages.

“But, BREAKING NEWS, we now know there IS an explanation for the Invisible Hand, which casts a whole new light on Adam Smith and his economic theories. And this sets up a whole new ballgame!”

This outburst made George pause. It sounded like they may be on the verge of a breakthrough, which meant he might finally be getting closer, please god, to a conclusion and the possibility of getting some sleep.

“You see,” continued the Director, “when Smith used the term The Invisible Hand, he didn’t know it was just an example of something that’s actually pretty common in the natural world. Something we now call Spontaneous Order.

At this, George pulled out another of his thoughtful ‘looks’ and touched his chin, to show he was interested.

“The best example of Spontaneous Order I know about is the starling murmurations on the Somerset Levels near where I live. Tens of thousands of starlings flying in synchronised patterns that look like a plume of smoke. They do it without a conductor or rule book. They somehow just feel the force.”

“They just do it!” Contributed Faye enthusiastically. “You see it with fish, too. When a shark attacks a school of sardines, they’ll make amazing patterns to confuse it.”

“Good example!” agreed the Director. “They protect themselves by being part of a bigger group. And this phenomenon isn’t just found in nature. Take Open-Source software, for example. Folks from all over the world working together on grassroots projects: Enthusiasts cooperate with each other to make cool and very complicated stuff without the need for a hierarchy of management calling the shots. And the result is all sorts of good things, like Linux, Wikipedia, Signal and WordPress.

Think about how slang words come to be accepted. No official committee decides what’s cool; they just naturally evolve and slip into our speech without a referee having to adjudicate.

“That sounds like something William Gibson might say,” offered Faye. “You know, The street finds its own uses for things and all that.”

“I was in one of Gibson’s films once.” Said George distractedly. “Johnny Mnemonic. Keanu Reeves. It wasn’t a great movie.”

The Director didn’t know what George was talking about; he was just happy to see him back in the programme and contributing again.

“Even scientific discoveries are often made by scientists tapping into one another’s ideas without a central hub. A lot of breakthroughs like this happen organically rather than through any sort of formal process.”

“Sounds spooky!” Said George.

“It is sort of spooky.” Agreed the Director. “The mathematician Steven Strogatz suggests that scientists find Spontaneous Order baffling because it seems to defy the laws of thermodynamics, which predict that things ought to fall apart rather than build into cohesive patterns. Yet, when we look through a telescope or a microscope, we see magnificent structures — galaxies, cells, ecosystems, human beings — somehow manage to assemble themselves. The enigma bedevils all of science today.

The Director quoted this from memory. George had ceased to wonder how.

“I should also say, FULL DISCLOSURE, that I’m not the first to suggest The Invisible Hand is an example of Spontaneous Order. That honour probably goes to an Austrian neoliberal oddball called Frederick von Hayek, who was, essentially, Adam Smith on steroids minus the moral scruples.

“Thatcher and Chilean dictator Pinochet loved him,” said Faye, unable to hide her contempt.

“I dislike him already.” Quipped George wryly.

“That she did.” Nodded the Director in the bartender’s direction. “Hayek believed the whole of human society was an example of Spontaneous Order but that this merely amounted to the sum of individual transactions, devoid of morals or emotions. Thatcher was more or less paraphrasing Hayek when she said, There’s no such thing as society.”

“She really said that?” asked George, genuinely surprised.

The Director nodded. “To be more accurate, she actually said:

“Too many people believe if they have a problem, it’s the government’s job to fix it. ‘I have a problem; I’ll get a grant.’ ‘I’m homeless; the government must house me.’ They’re casting their problem on society. And, you know, there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look to themselves first.”

“Jeez,” responded George, shaking his head at this cold, reductionist assessment of what Jean-Jacques Rousseau had called The Social Contract 200 years earlier.

“Hayek took Smith’s Invisible Hand and rebadged it as Spontaneous Order and then used this to explain why the free market was the only option for human progress. But he then went even further by insisting that greater inequality was good!”

“What a dick.” Said George contemptuously.

“I couldn’t possibly comment.” Replied the Director. “But, in essence, Hayek had noticed that when a society is controlled by politicians — as happened in Soviet Russia after their revolution — it soon turns into a totalitarian dictatorship, and he didn’t want that. So he took the idea of Spontaneous Order and used it to ‘prove’ that an economy works better when left to its own devices and why the concept of Greed is Good was a perfectly reasonable economic policy.Hayek’s ideas directly led to the development of the magical thinking of Trickle-Down Theory, later developed by The Chicago School, which the journalist William Blum memorably described as The principle that the poor, who must subsist on table scraps dropped by the rich, can best be served by giving the rich bigger meals.

“Other economists, like Karl Polanyi, profoundly disagreed with Hayek and suggested a better example of Spontaneous Order would be the trade unions, which came together to fight free-market theories such as Trickle-Down. Which is ironic if you think about it. But you don’t hear much about Polanyi because his ideas don’t fit quite so well with the GRiFTer agenda.”

“I’m beginning to see a pattern developing.” Said Faye.

“That turkeys don’t vote for Christmas?” asked George.

“Hayek won that argument and went on to inspire the Chicago School, which, in turn, influenced Nixon, Reagan and Thatcher. And the rest is neoliberal history.”

“…written by the victors…” added Faye again. “But it’s the victims who write the memoirs… Carol Tavris said that.” She qualified, speaking as the political science undergrad she was in her day job but not wanting to take credit for such a good line.

The Director nodded. “Yet, when Hayek, following Adam Smith, took the phenomenon of Spontaneous Order and bent it out of shape to fit his free-market agenda, he also took the humanity out of human interaction and replaced it with algorithms and a market that knew the price of everything and the value of nothing. And, thanks to him, we’ve ended up where we are now.”

Faye shook her head. She’d recently spent a whole term learning about Hayek and the neoliberal problems he’d caused, and this was bringing it all back.

“I’m no economist,” said the Director. “but even I know that if you deregulate a market and just let it rip, money and power will always stay near the top.”

“Which, I guess, was exactly the point the lady who designed Monopoly was trying to warn us about: that there’s only one winner and lots of losers.” Said George, remembering all those Christmases when he’d lost at that game.

“Which doesn’t sound much like Spontaneous Order to me.” Added the Director. “I mean, when you think of those starlings or sardines, they stick together because they instinctively know there’s safety in numbers. When attacked, they scatter, confuse their enemy, and reform once the danger is gone. And when you think about those peer-to-peer software enthusiasts busily making their open-source programmes, they’re not doing it for the money; they do it because they enjoy working in a team towards a shared goal. In fact, I’d say most of them do it precisely because it’s not about working for The Man. They do it for the simple love and satisfaction it brings, with no thought of personal, selfish gain.”

“Copitalism in action, which I’m pretty sure would be an alien concept to Hayek and his dickhead chums.” Said Faye forcefully, suddenly aware she might have overstepped the client/staff boundary.

The Director didn’t care and simply picked up where he’d left off. “So, in conclusion, Hayek and Smith were wrong to insist that a society is only successful when driven by the Invisible Hand of selfishness. This is the narrative pushed by the people upstairs because that’s the one that suits them best. In reality, their definition of this phenomenon is about as natural as a cancer slowly killing its host.”

“Mr. Smith said the same thing in The Matrix.” Added George for additional context.

“Well, he makes a good point.” Agreed the Director, “Because cancer cells may be an example of Spontaneous Order, they’re also an anomaly because they don’t build sustainable ecosystems. But, if you think about it, neither do they kill each other, which is more than you can say for Capitalism.”

“When you put it like that, it’s not exactly rocket science.” Said Faye as she digested the core components of this thesis.

“No, it isn’t.” Agreed the Director. “But it suits the GRiFTer agenda. Moreover, they don’t want us to know that genuine Spontaneous Order doesn’t fit the Capitalist narrative. In fact, whether they realise it or not, free market Capitalists fear anything resembling genuine Spontaneous Order. That’s because you can’t control it,and if you can’t control it, you can’t own it, and if you can’t own it, you can’t make money out of it. This is why Linux isn’t as popular as Windows, even though it’s fundamentally a better computer system: it isn’t now the world’s most used software because GRiFTers can’t make money out of it.”

“That’s so fucked up.” Was all George could think of to say.

“As I’ve said already, it’s a lot easier to encourage people to be greedy than it is to be kind. So, maybe Smith wasn’t describing the most efficient way of running a society, but just the most expedient: Theone that best fitted the Establishment’s needs at the time. The one that was easiest to implement. And maybe even Hayek desperately wanted his version of the Invisible Hand to be true, partly to make a name for himself but partly because he was genuinely concerned by what he’d seen happening in Russia. Either way, we’ve been dealing with the consequences ever since, which has inevitably led to the climate crisis we’re now threatened by.”

“Nice summary.” Agreed, Faye approvingly.

“Thanks. But hey kids, look at it this way.” He said, hoping to inject some optimism, “If I’m right about this, then it’s equally possible to make a case for a market that’s not driven by self-interest at all, but one in which people understand that helping each other is a better way of helping themselves, which I’d call mutual self-interest. It’s similar to what the Indian economist Amartya Sen said recently:

“We should not fall into the trap of presuming that self-interest is, in any sense, more elemental than other values. Moral or social concerns can be just as elementary.”

While this was quite a complicated idea, meaning he had to ask the Director to repeat it to make sure he understood, George finally felt they might be getting somewhere.

6.7. Let’s Stay Together

The Director was now in full flow, laying out the argument he’d had many times before, albeit only in his head.

“When Adam Smith was writing The Wealth of Nations, he did it from the comfort of Western Europe, which, at the time, was thought to be the greatest civilisation the world had ever seen. So, not surprisingly, he also thought that British merchants were a great example of the Invisible Hand. He therefore recommended that, with a few minor adjustments, Britain should just keep doing what it was good at, which, in 1776, essentially amounted to exploiting the poor at home and pretty much everyone else abroad.”

“Bastards,” said George.

“Seconded.” Agreed Faye.

“However, had Adam Smith cast his net a little wider while doing his research, he may have come to a different conclusion. As I explained to George earlier, if he’d been less dismissive of what he considered primitive cultures, he might have come closer to agreeing with Adam Ferguson’s theories.”

“Really?” asked Faye, a little surprised, given she knew a little about Ferguson’s ideas.

“Sure!” replied the Director. “Give him his due; Smith looked at the Ancient Greeks, the Romans and even Chinese culture to see how they traded, but he completely overlooked the barter systems used by agrarian societies because he didn’t think they had anything to offer. He might have been a great thinker for his time, but he was no anthropologist. I mean, he called Native Americans savages.”

George was not impressed.

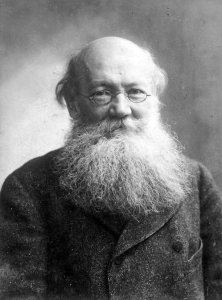

“Had he looked a little harder, he might have realised that a selfish Invisible Hand was only one of many conclusions he might have come to. But he lacked all the ingredients he needed to make that picnic. I mean, imagine if he’d known about Peter Kropotkin!”

“Doctor Kropotkin?” Asked George, surprised. “Isn’t he a character in my Super Mario video game?”

“I’m not sure, George,” replied the Director. “I’ll look into it. But the Kropotkin I’m thinking about looked like Father Christmas but was actually a Russian Prince who’d spent years studying animals in Siberia and developed some revolutionary ideas that might have caused Adam Smith to rethink his theories.”

“I like where you’re going with this.” Complimented Faye, as she knew Kropotkin was part of a module she’d be studying in her next term.

“Kropotkin had seen how animals in the wild cooperated with each other. Most were members of the same species, but sometimes different types of animals helped each other out, foraging for food, hunting in packs, warning each other of predators and even building communal nests. All of which might have been considered Spontaneous Order had Smith known about it. Moreover, it’s now obvious that this form of Invisible Hand creates stable and self-regulating ecosystems that Adam Smith would have been blown away by. It was certainly a long way from the dog-eat-dog picture of the natural world the sociologist Herbert Spencer had in mind when he coined The Survival of the Fittest. Spencer hijacked Charles Darwin’s and Adam Smith’s ideas to support his right-wing ideology, particularly his idea that human advancement relied on competition. Kropotkin disagreed: He knew the laws of nature applied just as much to humans as they did to animals and that successful societies were, therefore, built on cooperation. Something I like to think of as the survival of the kindest.”

“Nice.” Said George approvingly.

“So I’m sure if Smith and Kropotkin had met, they’d have had much to discuss. Unfortunately, it never happened because they were born almost a century apart. However, if they had met, Kropotkin would have been able to describe what a hundred years of Capitalism and the industrial revolution had achieved. A sort of half-time highlights reel.”

“Like a soccer manager describing the match so far.” Suggested George.

“A mismatch, more like,” said Faye, who already knew the score.

Picking up the theme, the Director explained, “Yes, he’d point out that GRiFTers United were 5-0 up, that environmental disaster and social injustice had been running rampant down both wings, and the laissez-faire tactics of the opposing coach were stacking the odds massively in favour of the wealthy elite.

“Smith wouldn’t have been too impressed.” Suggested George.

“You’re right,” agreed the Director, “so I’m pretty sure he’d have listened to Kropotkin’s suggestion of switching to a more structured Mutual Aid formation based on teamwork rather than individual flair.”

By this point, the Director’s contrived allusion to soccer management had become far too niche for George to follow, so he returned to something more prosaic.

“So I hope I’ve explained how we can swap out Capitalism for something better, something I think Adam Smith would recognise and, being a well-meaning guy, would agree with. Hopefully, he’d see his precious Invisible Hand wasn’t necessarily driven by self-interest and that maybe his mate Adam Ferguson was more on the right track with his vision of a kinder society. Smith might even have realised the monster he’d created was capable of destroying the planet and that it might have been better if he’d kept his big mouth shut.

6.8. Bring Me A Higher Love

At the end of this little speech, the Director drained his glass with a satisfied gulp.

“You look as if you could do with a little Mutual Aid yourself,” suggested Faye, who’d been quietly polishing the same glass for five minutes. “Care for a top-up?”

“That’s a great idea!” Responded the Director with a smile. “And the same for my friend here, and have one yourself.”

“So, I get it,” said George, energised since the conversation had turned more upbeat. “Maybe Adam Smith got it wrong. He was looking at a world where wealthy people were already doing very well for themselves, so he assumed that was just how life worked.”

“Precisely; to be honest, the last thing Smith wanted was to give those psychopaths at the East India Company an easy-to-follow guide that explained how to switch from slow and restrictive Mercantilism to the new, improved and much more profitable Capitalism.In fact, he hoped his book would reform the East India Company altogether. Some hope. Seeing how much profit they could now make, the politicians who ran the show just filleted the parts of The Wealth of Nations they didn’t like and filled their boots with whatever was left.”

“Bastards.” Muttered Faye.

“That’s what I’ve been saying all night!” Chuckled George, though he wasn’t sure what this had to do with boots or who owned the boots. “I get it: Smith screwed up, but Spontaneous Order can still save us by organising us into a more cooperative society. So what do we do next? Should we just hang around and wait for inspiration? Tell me before I die of suspense — or alcohol poisoning, whichever comes first.”

The Director was fond of this young man, and this encouraged him to press on. “Sure,” he said, “so we’ve talked about how Capitalism isn’t some grand scheme designed by the Illuminati, but just a lot of little dragons like me and you who are too greedy to give up our lifestyle without knowing there’s something better waiting on the other side. And as I’ve tried to explain, I believe that Copitalism is that something better we’ve been looking for.”

“Cool. So, if I was ready to sign up for a Copitalist lifestyle, where do I start? Where are the companies I can buy these Copitalist things from? Do they actually exist?”

“Sure they do.” Reassured the Director.

“Really,” asked George, looking around. “Plenty of brands claim to be saving the planet, but when you look more closely, you realise they’re as bad as the rest.”

“Just so much greenwashing.” Said Faye cynically.

“That’s very true,” agreed the Director. “At the minute, you have to be very careful because there’s a hell of a lot of shady marketing around trying to hoodwink you into buying stuff you think is green when it’s nothing of the sort. The GRiFTers boast about their ESG credentials and exaggerate how ethical they are, and we put up with it. But if we started to take more responsibility for the things we buy and reject the brands that lie to us, they’d soon change their ways.”

“But would they?” asked George sceptically. “Will capitalist businesses ever behave honestly?”

“Sure!” replied the Director. “Would you believe me if I told you that a hundred years ago, there were lots of Copitalist companies in the UK?”

“Are you sure?” Asked George again. “You’re telling me there were trustworthy businesses even before shoppers had legal protection?”

“Yeah, that’s what I’m saying. It’s incredible to think that, back in Victorian times, many businesses in the UK rejected the Capitalist model. What’s more, they were very successful, even though they didn’t consider profits their sole reason for existing.”

“Wow!” said George.

“Unlike most big businesses today, that are only interested in keeping their shareholders happy, these early Copitalists prioritised their social and ethical responsibilities. They saw it their duty to provide a good standard of living for their employees and invested a large proportion of their profits into it.”

“19th Century Copitalism in action!” Exclaimed Faye in surprise.

“Sounds great, but they couldn’t have been all that successful,” Counter-challenged George ruefully, “or else I’d have heard about them.”

“You probably have,” replied the Director with a smile. “I mean, I’m sure you’ve eaten Quaker Oats, and I know you like British chocolate because you eat it all the time, and Cadbury’s, Fry’s and Rowntree’s were all Quaker businesses, and, if I’m not mistaken, those shoes you’re wearing are Clarks?”

“That’s right. Wallabees”, confirmed George; “Super cool. We all wear them in LA.”

“Well, once upon a time, they were a Quaker firm, too.”

“I did not know that.”

“Yep. And how about GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson before Big Pharma bought them out. And Barclays and Lloyds Bank before they sold out to the financial system, which is now killing us. Or what about Unilever? It’s one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, but in 1888, when a Quaker called William Hesketh Lever began manufacturing soap in Liverpool, it was just called Lever Brothers. He built his business on simplicity, social responsibility, and ethical practices. As well as running a profitable business, he aimed to improve the living conditions of his workers and their families, so he built an entirely new town called Port Sunlight in the countryside on the banks of the River Mersey, where over 3000 of his employees lived. They enjoyed beautiful architecture, green spaces, a hospital, schools, a church, shops, a swimming pool, a theatre, a gym and an art gallery. Pretty incredible for 1888!

“Another Quaker called George Cadbury made chocolate in Birmingham. In 1895, he moved his factory 5 miles out from the polluted city centre to a model village he’d built called Bournville.

“Bournville housed around 2,500 employees in high-quality housing inspired by the Arts & Crafts movement. Like Port Sunlight, it also had green spaces, a junior and secondary school, a swimming pool, playing fields, a library, a reading room and even a musical tower!

“The cost of creating these model villages was enormous, but that wasn’t the point. Unlike today’s multinationals, these Quaker businesses weren’t all about the money. They had what we’d now call ESG genuinely baked into their culture a hundred years before it was fashionable. And it wasn’t just a way to greenwash their businesses. They even pioneered gender equality, allowing women to be top managers. These businesses made high-quality products, were respected pillars of the community and contributed enormously to broader society. All of which made them highly trustworthy. Which, in itself, was an excellent way to differentiate from less reputable or reliable competitors. As a result, they enjoyed even more success.

“The point I’m making is that Quaker entrepreneurs saw business as a way to serve something higher than just profit, and, like the King of Bhutan, they had ambitions beyond just wanting to be filthy rich. They had other priorities.

“As you say, Faye, they were a perfect example of Copitalism, so it’s a tragedy that most of these Quaker businesses were gobbled up by the Dragon and sold to the GRiFTers. But a few still survive, and it’s time we brought more of them back.

“And there are plenty of modern examples of this sort of thing. Think of mutual societies, cooperatives, not-for-profits, charitable organisations, community interest companies and employee-owned businesses like the John Lewis Partnership / Waitrose / Peter Jones share their profits with their partners or the hi-fi chain Richer Sounds, which handed over 60% of the business to its staff. And brands like Patagonia.”

“Tell me about Patagonia.” Invited George, “I’ve got a bunch of Patagonia gear back home.”

“Well, until 2022, they were a private company, which meant they didn’t have to worry about giving institutional shareholders their pound of flesh. They could do whatever they liked, which, in 2020, included sewing labels in their clothes saying Vote the Assholes Out – because they didn’t want Trump to be re-elected. This attitude made them even more popular, making their owner a billionaire! This horrified him, so he gave the business away to the Holdfast Collective, a trust dedicated to fighting the environmental crisis. Since then, their sales have continued to grow because people want this sort of authenticity and courage from their brands. More business owners must realise that being good for the planet is good for business. And it’s not as though the climate crisis is going away. In five years, it will be a lot worse than it is now, so the successful companies will be the ones that tried to do something about it early.”

“So, you’re saying is we should buy from independent Copitalists whenever we can and avoid Global, Rent-Extracting, Financialised Tax-Evading GRiFTers!“

“That’s exactly what I’m saying.” Agreed the Director. “But then there’s the Ben and Jerry’s of this world.”

“Ben & Jerry’s? Asked Faye. “They used to be cool — before they sold out to Unilever.“

“That’s right,” Agreed the Director. “But they’ve been a thorn in Unilever’s side ever since because they don’t play the Capitalist game. Unilever finally gave up on them a few months back and is selling them, so it’ll be interesting to see what happens next. It’s hard for businesses like Ben and Jerry’s when they’re trying to change the system from the inside. They are pressured by institutional investors to make more profits while trying to protect their reputation for being the good guys. Institutional investors are only interested in the bottom line, so they have zero morals, or, to be more accurate, they are AMORAL because they’re autonomous entities, like machines, devoid of human emotion: their only purpose is to maximise profits. So avoid them whenever you can.”

“Gotcha.” Agreed George.

“And while we’re at it, let’s remember the millions of people, like doctors, nurses, teachers and charity workers, all making a fraction of what they might otherwise earn if they’d chosen a proper job”, said the Director, showing his disdain for what, in the commercial sector, might be considered a proper job. “These people don’t work to make as much money as possible; they look for satisfaction and reward from helping others.”

“They’re Copitalists too!” exclaimed Faye, realising this concept applied to a broader definition of society than that offered by capitalism.

The Director was pleased to see the full implications of his idea were slowly being absorbed. “Where would we be if we took our cue from teaching professionals who want to do more than just make money or from business owners who know that being philanthropic, like the Quakers, makes good business sense?And what could we achieve if we stopped pandering to the GRiFTer institutions and took more care in how we spent our money? I’m telling you, it would have massive repercussions throughout society. It would put the investment banks out of business, the bond and currency markets would dry up, and those poor offshore tax havens would have to find new ways to grift a living. But, as these parasites add nothing to society anyway, we wouldn’t even notice they’d gone, and the world would be infinitely safer and better off.

“You go, Sir!” shouted George enthusiastically, caught up in this speech. The Director had been on a roll for a while now. George and Faye exchanged a smile, appreciating his energy and passion.

“Why is this so hard to imagine?” He continued. “Why am I considered eccentric for suggesting such a thing? After all, the world would be much better off, and we wouldn’t be slowly killing ourselves.

“Of course”, continued the Director, hardly stopping for breath, “the GRiFTers would argue that without their investment, the economy would grind to a halt, thousands of companies would go out of business, and there’d be no money to invest in new technologies. But that’s a false argument: Without the GRiFTers, we’d stop investing in things we didn’t need in the hope of making easy money and only invest in what was useful to us. Remember, The New Deal or The Welfare State only happened because the banks and stock markets had failed. We don’t need banks; we need a new vision for how to succeed.

The Director paused momentarily to savour the aroma of his whisky and mentally construct the final point he wanted to make.

“If Patagonia can explore ways to escape the Capitalist trap, so can millions of other businesses, especially if their customers are willing to support them. It’s all about quality over quantity. Buy less / Buy better.

“The GRiFTers don’t want you to think like this. Who knows what would happen if we realised we held all the cards? It wouldn’t take a revolution to overthrow the bourgeoisie; we just need to stop playing their games and demand a simpler, safer, healthier world instead.”

“Now we’re getting somewhere.” Confirmed George with a degree of satisfaction. “So what do we do now?”