George and the Director had sat in the gradually emptying studio for over an hour. During this time, various heads had popped around the door to say goodnight, some waving a cheery bye! Others, seeing the Director in deep conversation with the leading man, decided it wiser not to interrupt.

The Director drained the last of the cheap champagne and realised he felt a little jaded. It was the end of a long day, and he’d put a lot of effort into an impassioned speech. But mostly, he was tired because whenever he spoke about the imminent climate disaster, he felt drained and depressed. It was a horrible thing to have to keep confronting.

After perhaps a minute of awkward silence, George, slightly embarrassed and a little drunk, thought he’d better break the moment. “So I guess I’ll be getting a cab.”

Suddenly, returning to the room, the Director picked up on something he’d been quietly mulling over. “Have you ever seen those Linklater films, George? Before Sunrise and Before Sunset?”

“And Before Midnight, replied George, pleased he knew the movies to which the Director was referring. “Wonderful, aren’t they? Why do you ask?”

“I like them too,” agreed the Director. “So, instead of taking a cab, why don’t we walk back along the river to your hotel. You’re at Battersea Power Station, aren’t you?”

“That’s right,” confirmed George.

“Great, and while I appreciate I’m no Julie Delpy, you’d make an excellent stand-in for Ethan Hawke, and we could walk and talk, get some fresh air, a little exercise and shake off the booze. This way, I can tell you the rest of my Dragon story because I’ve only scratched the surface. What d’ya think?”

“Of course!” replied George enthusiastically. “That sounds like a great idea,” He was genuinely relieved because he still didn’t have the answers he was looking for, and he felt privileged to be finally spending quality time with the great auteur.

“Grab your coat then,” said the Director, cheerily throwing his own jacket over his shoulder while walking towards the back of the set. On his way out he patted the backs of the few remaining technicians still working.

The cold air hit their faces as they stepped into the dark. After the heat of the studio and the glow of the alcohol, they could feel the autumn dampness being drawn into their lungs, so they both pulled their collars over their necks in classic Hollywood style.

“You see,” said the Director, ready to resume his dissertation, “We are living in a sort of dream, and right now, we’re sleepwalking towards a cliff edge. It’s as if we’ve been given sleeping pills, but, spoiler alert, we’ve been only too happy to swallow them. In his book Brave New World, Aldus Huxley had a similar idea, only he called his sleeping pills Soma.

“In this collective dream, we’re driving new cars and flying first class to exotic destinations, while our kids happily play in our well-kept gardens while we tell our friends how successful we are. But it isn’t real. It’s just a dream we keep repeating in our heads.

“We believe that when we finally buy these things, we’ll at last be happy, and our friends will envy us because, after all, that’s what the advertising has promised us.”

George looked at the Director from the corner of his eye to check he was being serious.

“I know it sounds like the plot of The Matrix, but I can assure you what I’m describing isn’t a million miles from what’s really happening in our day-to-day lives. Marx called it Commodity Fetishism. Mark Fisher called it Capitalist Realism. That’s why The Matrix was so popular: because, on some level, people knew there was an element of truth to it.

The Director noticed George was still looking sceptical. “From the look on your face, you’re probably thinking I’m a conspiracy theorist, and in a minute, I’m going to convince you the moon landings were faked and Donald Trump won the 2020 election. But, in a way, what I’m actually saying is even more outlandish than that because, unlike in The Matrix, this isn’t science fiction. I honestly think we’ve chosen to stay asleep and enjoy our consumer dreams rather than wake up and face the truth.”

“Come on, Sir, are you actually being serious? Are you telling me we’d rather die than face the facts?” George wasn’t buying it.

“Yes, George, that’s exactly what I’m saying. Remember the Dragon and how you had to show him he was an addict and needed therapy?”

George nodded, recalling that scene.

“Well, the same thing happens in real life — and it’s going to take a lot for me to make you realise you’re an addict.”

“I’m going to need some convincing.” Confirmed George. “It sounds like the screenplay of every bad dystopian movie I’ve appeared in over the past ten years!” He continued, charmingly self-deprecating.

“I know,’” replied the Director. “It always does. And the deck is stacked against me. So this is what I’m going to do: First, I’m going to explain the problem: SPOILER ALERT, It’s Capitalism stupid. Then I’m going to take Capitalism off its pedestal and walk you through its less-than-stellar history. Then I’m going to show you just what an out-of-control monster it’s become. And finally, if you’re still awake and you’ve not thrown me in the river, I’ll offer a few ideas on how to save the world”.

“Holy Cow! That sounds like a lot of information!” thought George. “I hope I can take it all in.” But what actually came out of his mouth was, “Super interesting! Can’t wait!” While enthusiastically clapping his hands together. “Let’s get to it!”

2.2: Working for the Man

“OK,” said the Director, buoyed by George’s continued enthusiasm while pulling his scarf under his chin to keep out the increasingly damp night. I think it’s safe to say that Capitalism has been the predominant driver of world affairs for the past 200 years. It’s bigger than me, and you, and it’s bigger than individual countries. It’s even bigger than religion.

“I suppose you could argue that China or Russia aren’t Capitalist systems, but you’d be wrong. Russia is a kleptocracy of rampant corruption, which, you might say, is the logical end state of any capitalist system. As for China, it may still be run by the Chinese Communist Party, but that’s in name only. The reality is that it only became the world’s second-largest economy when it started CHASING MONEY!”

The Director emphasised the final two words of this sentence with relish.

“This is hardly contentious. There’s an army of right-wing economists and politicians who’d be proud to endorse every word I’ve just said. They’d also argue that Capitalism is behind the increase in global life expectancy, the provision of education, and the lifting of people out of poverty. And, that may, indeed, be true but the fact is, we’ll never know how things might have turned out if we’d taken a different path.

“So I hope you can see that our little movie isn’t a polemic against Capitalism. This isn’t an ideological rant. It’s not even political. I’m not anti-anything, apart from maybe being anti-mass-extinction. But, unless there’s a massive shift away from free-market Capitalism in the very near future, that’s what we can expect. This is important to emphasise because, when it comes to criticising Capitalism, people get defensive very quickly, and if we do that, we won’t get anywhere. Sure, I might be rude about the really dangerous Capitalists that run our daily lives. They’re a specialist group I call the GRiFTers, and there’s a reason I’ve given them that name, which I’ll explain later, but even blaming these GRiFTers is a pointless exercise because they’re really only a product of the system that’s killing us, so it’s pointless blaming them. I might agree with Marx about certain things, but that doesn’t make me a mad Marxist. I’m not motivated to bring about the end of Capitalism. I’m not into the class struggle; I’m just a human that is deeply motivated by the idea of not dying too soon. Marx saw the need for class war, but I disagree. I mean, why go to the trouble of killing each other when the climate is going to do the job for us? The climate doesn’t discriminate, you see. It’s as happy to kill the rich just as much as the poor, so it’s important we all have a good think about this and see the futility of turning this into a political argument.

“Perhaps, at one time, the GRiFTers could make an argument for the inequalities and injustices of the Capitalist system. If you’re lucky enough

to be middle class and living in a Western, developed country, perhaps a little inequality is a price worth paying for improvements in living standards and life expectancy: enter them in the asset column of the global balance sheet. However, the benefits of capitalism have reached their limits when you look at the debit column and see an item in red labelled Mass Extinction Event.

It’s funny: Lenin thought the middle-class bourgeoisie would die at the hands of the Bolsheviks when actually, we ended up being swotted like an irritating housefly by an ecosystem that’s had enough of our arrogance. Who knew Marxism and climate change had so much in common?”

“That reminds me of something.” Said George, searching through his somewhat addled memory banks like a librarian flicking through a Rolodex.

The Director waited patiently. He could almost hear the cogs turning in George’s brain.

“That’s it!” Said George eventually, “It’s like that Aesop’s Fable I was taught in kindergarten when the North Wind and the Sun made a bet on which could force a man to take off his coat.”

“Really?” Asked the Director, genuinely intrigued. “How so?”

“Well,” began George, trying hard to recount the story accurately. “The North Wind and the Sun were arguing about who was stronger. So they agreed to see which of them would be the first to get a passer-by to take off their coat. The Wind tried first by blowing a gale, but this only made the walker look up to the sky and wrap their coat around them even tighter. Then it was the Sun’s turn, and when his sunshine warmed the man’s back, he quickly took off his jacket and fell asleep in the shade of the nearest tree.” George finished his story with a little bow.

“So are you saying that the unusual weather we get these days will persuade us to change our ways?” Asked the Director, still somewhat bemused.

“Well, I guess so,” agreed George, sounding a little uncertain, “But what it really made me think is that The North Wind is like Communism that wants to remove the coat through force, while the Sun gets the man to take off his coat because it’s what he wants to do. I always thought the moral to that fable is that persuasion is more effective than violence.”

The Director was stunned. George seemed to have a way of reducing complex ideas into language and imagery a child could understand.

“That’s exactly right!” Cheered the Director, patting George on the shoulder. We aren’t trying to start a violent revolution. We need people to see that a better future is waiting for us if we are willing to take a look. The problem is, how do we get people to see?”

George shrugged and shook his head a little.

“You see,” continued the Director, hoping to persuade George that the ideas he was offering were not to be feared but to be embraced. “Capitalism is a sort of social operating system, in the same way that Microsoft Windows is a computer operating system. One determines how a computer works, while the other determines how society works.

“Come to think of it, this is a pretty good analogy on several levels,” said the Director, thinking aloud. “Because, like Microsoft Windows, which runs on about 80% of the world’s PCs, Capitalism might be the world’s dominant economic system, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the best.

“For a long time, Windows was just one of many operating systems you could choose to power your PC. It wasn’t necessarily the best, but it was the one everyone else seemed to be using, so we all used it without thinking. Actually, the Microsoft system was necessarily the best, but Bill Gates and his team were the most politically astute, ruthless and business savvy, cutting the best deals with retailers, shutting out or buying up the competition, pinching the better ideas from other operators like Apple and of course, spending shitloads of money on advertising. As a result, it eventually came to dominate the market even though, in many ways, it wasn’t the best system.

It’s exactly the same scenario with fossil fuels. We could have transitioned to cleaner, renewable energy decades ago but that didn’t happen because the GRiFTer oil and gas companies, which had infinitely more money than their smaller, greener competitors, simply shut them down any threat to their magic money tree. Their cash-cow. They maybe even bought out and mothballed these competitors despite knowing this would be bad for the planet in the longer term and with it, the likelihood of mankind’s survival. A little bit of climate change wasn’t going to stop the legacy energy firms from maximising their profits. I can assure you, George, I am not exaggerating or making any of this shit up.”

In the face of this onslaught, George thought it best to keep his mouth shut and just keep walking, though he did think a few PowerPoint slides might have helped.

“And, just like Microsoft Windows,” continued the Director, “Capitalism was designed for a world that’s very different to the one we live in now. The internet hadn’t been invented when Bill Gates was supposed to have said, ‘640K (of computer RAM) ought to be enough for anybody. So we can perhaps forgive him his little oversight. Things were very different in the early 1980s when personal computers were just finding their way into people’s homes but the same can’t be said for fossils fuel. But it’s harder to forgive the fossil fuel companies who suppressed any information that might threaten their profits. We’ve known about the dangers of releasing carbon into the atmosphere for a hundred years, but our economic system preferred to ignore them; which wouldn’t be so bad if we were still just talking about obsolete computer software. I’m sure we could all live with the inconvenience of a computer that takes ten minutes to boot up. But with free-market Capitalism running the show, backing the fossil fuel industry and suppressing any competition, we all end up being boiled alive!”

George sighed as if deflated by the enormity of the problems being described to him. For some time, he’d wondered whether it might have been better to catch that cab back to his hotel. Instead, he was trapped, walking along a dark, narrow towpath with a highly animated, diminutive but still slightly intimidating Scotsman. For George, there was nowhere to hide.

2.3: Don’t Look Back In Anger

The Director noticed that George was looking a little browbeaten, so looked to see how he could move the discussion on to something more upbeat. “But, like I said before, we aren’t going to fix this problem by simply blaming the Capitalists. That’s a waste of time and probably what they’d want us to do anyway.

“It’s too easy to blame ego-maniac CEOs and greedy bankers and corrupt politicians, satisfying though it would be to throw rotten cabbages at them. The GRiFTers are just a symptom of a system built on Status, Power & Money (S.P.A.M). Since their first day at public school, these CEOs have been brainwashed into believing that Greed is Good and that, perversely, by being greedy and selfish, they were somehow contributing to the creation of a more successful and prosperous world where a rising tide raises all boats. I shit you not. So, how can we blame them for turning out the way they have? Sure, there are winners and losers in the game of Capitalism, but we have to address the game itself, not the players.

“Western society celebrates Status, Power & Money (S.P.A.M). We look up to the greediest of us all with envy as though they are the most outstanding examples of what we could become. GRiFTers like Musk, Bezos, Zuckerberg, and the half-man, half-goat that is Richard Branson bathe in celebrity status, venerated as some sort of latter-day saints. Yet, all of them are deeply odd individuals who just happen to have been in the right place at the right time. They had wealthy parents, or they bet on red at the correct spin of the roulette wheel. But, of course, they’ll claim it was skill and insight that got them where they are today. But, for every Bezos, there are a dozen GRiFTers we’ll never know about because they bet on black. Without good fortune, Musk, Bezos, and Zuckerberg might now be working at the check-out of our local supermarket, and no one would give them a second thought. As the old joke goes, what would Zuckerberg be like now if he wasn’t a billionaire?

Answer: A virgin.

“Middle managers like George in the movie aspire to be like these narcissistic oddballs. Kids watch their YouTube videos, listen to their podcasts, try to emulate them, and want to be like them one day. I mean, people voted for Donald Trump, for krissakes. He was the President of the United States! Doesn’t that tell you just how distorted Capitalism has become?”

“Amen to that,” confirmed George.

“So who can blame the Capitalists for just following orders? They’re just fulfilling their sense of entitled destiny. They’re not the problem; they’re just a distraction.”

“You see, George, and this is the most important thing I will say today.” To emphasise the point, the Director stopped and grabbed George’s arm to make sure he stopped as well, “The problem isn’t OUT THERE, pointing to the skyscrapers of London’s dockland in the distance. The problem is IN HERE“, which he emphasised by beating his chest a couple of times with his fist. It’s the Capitalists inside us all that make the GRiFTers rich. We all have a selfish dragon inside, and we’ve all got to slay it if we want to survive!”

“Wow!” thought George, hoping he’d finally reached the critical point of conversation that would answer his question. “This is the bit I don’t understand. I now know the Dragon has an unhealthy addiction to power, and he doesn’t want to give it up. But I don’t understand how that same Dragon I hate would be the same Dragon I love in myself.”

“Well, that’s the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question,” replied the Director. “Patience, my boy, all will be revealed in the fourth act. But first, we need to explore how Capitalism got us into this mess in the first place. Deal?”

“Deal,” agreed George, inviting the Director to continue while reflecting on the fact he wouldn’t normally get out of bed for a paltry sixty-four thousand dollars.

2.4: Money, Money, Money

“But can we really blame Capitalism?” Asked George, pushing back on what he thought was something of an apocalyptic statement. “I mean, are we really about to be boiled alive?”

“Yes!” shouted back the Director emphatically, unwilling to take back his statement. “And here’s the proof: we’ve got to the point in our evolution when we’re about to commit suicide, and you don’t have to take my word for it. This existential threat we’ve created even has a name. It’s called The Anthropocene, which describes the period we’re currently living through, you know, with its exponential population growth, industrialisation, intensive agriculture, deforestation, and greenhouse gasses. All of this means that our planet – the one we’re currently standing on – is heating up like a rotisserie chicken. Scientists call it the Great Acceleration, or, as I like to think of it, Capitalism’s club foot putting the pedal to the metal. The ecosystem of our precious planet is like an elastic band that’s been stretched as far as it can go. It’s about to snap back in our faces, and I can tell you, that’s going to leave a nasty mark.

“And I know what you’re wondering.” Continued the Director. “You’re wondering whether the Anthropocene could have happened under a different economic system. Could these conditions have only been created by Capitalism? And that’s a fair question, and all I can say is we’ll never know, but what I can tell you is that what we are dealing with now and this is most definitely Capitalism’s fault.”

This caught George somewhat by surprise because he’d actually been wondering whether Woolly Mammoths might have lived during the Anthropocene Age, suggesting this part of the Director’s thesis might have gone over his head.

“What I do know is that if right-wing economists and politicians are happy to claim that Capitalism has been the key driver of human activity for the past 250 years, then they must also take responsibility for the misery, pollution, and environmental destruction as well.

George concurred with a quick nod of his head.

“Let’s be frank: Capitalism has caused global warming because, to succeed, Capitalists need to keep making profits and to do that, they need to keep growing their business. That’s a baked-in rule of the system. This inevitably means that, since the Industrial Revolution, more and more fossil fuels have been burned to feed this relentless growth. And because economies must keep growing, the problem keeps growing, too.

“And it doesn’t take a genius to know that while the world might be a very big place, it isn’t infinite and, eventually, it must run out of the materials Capitalism needs to sustain itself: if it doesn’t asphyxiate itself first. “The rules of Capitalism mean that rival businesses are in a never-ending competition with each other, with the winner grabbing as much of the market as it can until there’s nothing left. Presumably, the winner is the last man standing. Nothing gets shared. Nothing gets rationed.

“You’ve just described a game of Hungry Hippos!” Observed George innocently surprised.

“That’s right!” agreed the Director. “Personally, it reminds me of that TV show Supermarket Sweep. Do you get Supermarket Sweep in the States?”

“Er, I’m not sure,” replied George. “I don’t think so.”

“Does the name Dale Winton mean anything to you?” persisted the Director.

“Was he in The Power of the Dog?” asked George hopefully.

“I don’t think so,” replied the Director. “But never mind. Where was I?”

“Capitalism.” Replied George. “Capitalism and competition.”

“Yes, yes!” replied the Director, climbing back onto this train of thought. “Good to see that you’re paying attention, George!”

George appreciated this compliment.

“The problem with competition, you see, is that it means everyone is out for themselves, and that, quite frankly, is a recipe for disaster.” Explained the Director, musing on this momentarily and shaking his head almost in disbelief. “I mean, where else do we go about trying to beat someone else at something? We might want to beat someone at soccer or table tennis, but we all shake hands and go for a beer afterwards. But when we’re playing at Capitalism, if we win, we put food on our plate, but if we lose, we starve. What’s more, if we win, we’re not just putting food on our family’s plate but taking it off somebody else’s. Whoever thought that was a sensible way to run a society? If a monkey hoarded more bananas than he could eat while leaving the other monkeys to starve, scientists would say the monkey was psychopathic and try to figure out what was wrong with it. When humans do it, we put them on the cover of Forbes magazine.”

This description sounded weirdly distorted to George; he couldn’t believe Capitalism could be this bad, but he couldn’t find a flaw in the Director’s argument either. He even began to wonder whether the booze and fatigue were playing with his head.

“Anyway, the point is,” continued the Director, who sounded as though he was beginning to wind up this particular cogitation, “All this need for profit and growth and competition means we’re trying to get a quart out of a pint pot, as we used to say when I was a kid. Do people still use idioms like that?”

“I think we use memes instead these days,” corrected George, happy for the chance to contribute.

“I stand corrected,” replied the Director, bowing slightly.

“But what is relevant is that we’re taking more from the Earth than the Earth can give, and it’s killing us. Capitalism is a zero-sum game, and, in the end, nobody wins. But because it seems to have worked in the past and no one has yet suggested a better idea, and because no one seems able to stop it, it just keeps growing, like cancer, pushing us closer to the cliff edge.”

“Jeez!” replied George, unsure what else to say. He could see the Director was committed to what he was saying, but still couldn’t quite believe all this could be true.

“If what you say is accurate,” suggested George tentatively, “perhaps the problem isn’t knowing all of this but not knowing what to do about it.”

“That’s right.” Responded the Director, pleased they were still on the same page, more or less.

“And I’ll come to that, but first, if we want to find the way out, we need to know how we got here in the first place.”

The twinkling of reflected lights danced on the water, offering a soothing contrast to the bright studio lights they’d endured all day. They paced briskly to match the rhythm of their conversation but, for a moment, fell into their own private meditations. However, it wasn’t long before the Director, concerned that he still had much to get off his chest, returned to his thesis.

“Alright, I’ve explained how Capitalism is out to kill us and how we’ve got to stop it. But before I do that, I think a little historical context is needed because I want to disabuse you of any ideas you might still harbour about Capitalism somehow being ‘the only way.‘ The Director used his fingers to describe speech marks as he said this.

“This isn’t something we’re generally taught in school, and we’re definitely not allowed to suggest that Capitalism is just one alternative out of many.

“Funny, but I guess that’s right.” Confirmed George, turning this over in his mind for the first time.

“So, I’m going to take you back to the origins of modern economics if you’re up for that?”

“Do I have a choice?” asked George, being playfully sarcastic.

“Not really,” replied the Director, equally tongue-in-cheek.

“Now, if we look at how Capitalism is the big deal it is today, it’s easy to assume it’s been around forever. But, actually, it’s quite a recent phenomenon.

“People only started thinking about it towards the end of the 18th Century, which, to put it in context, was around the same time as the American War of Independence (1776) and the French Revolution (1789-1799). Before that, in the mid-1700s, countries traded with each other using a weird system called mercantilism, andbefore that, what little international trade there was based on good old-fashioned feudalism.

“So let me quickly give you the back-story to these systems for a little context. First, as I say, there was feudalism, which lasted for about 500 years. It was simple patronage where the king or queen would literally buy the loyalty of their barons by giving them land. British politicians still do it today when they ennoble their financial backers and put them in the House of Lords. Anyway, within the feudal system, trade was relatively modest and based mostly on barter rather than money.”

“In the 1500s, as international trade became more common, the feudal barter system morphed into something called Mercantilism, in which individual countries specialised in making and selling specific goods. So England became a centre for woollen goods, the Dutch produced excellent lace, and the Portuguese made the best wine; and, out of this, an elaborate system of ‘swapsies’ developed where the French exchanged fine furniture for English wool and the English swapped their wool for Portuguese wine. Unfortunately, as in any game of Happy Families, everyone tried to hold on to their best cards so it all became entirely self-defeating. Eventually, the French got sick of it and decided they would benefit more if they traded more freely with other countries, even if these other countries did well out of the deal as well. And what became known as laissez-faire economics was born.

“Fast forward to 1776, and my fellow countryman, the great Adam Smith, whom many call The Father of Capitalism. He wrote The Wealth of Nations, which describes the underlying forces influencing how people and countries traded with each other. With me so far?”

“All of this is very interesting,” replied George enthusiastically, relieved now to be talking about history rather than politics.

“Shall I continue?” asked the Director.

“Please do.” Replied George.

“OK. So Smith thought he could see an underlying pattern to the way people were trading with each other, and, in particular, he believed that when people were motivated by selfishness, some sort of inexplicable alchemy occurred, which meant that, eventually, the whole of society would benefit. He called this the Invisible Hand of the Market.

“For example, Smith thought that if a businessman wanted to expand his business, and, by the way, business owners at this time were almost exclusively male, he’d need to hire more workers. To do that, he’d need to pay them more than whoever else was employing them at the time, which, in turn, would mean the workers would become wealthier too. Sounds like a win-win, right?”

“Sure does,” confirmed George.

“Unfortunately, there was just one tiny little fly in this ointment because, for this beautiful system to work, the workers needed the freedom to find another gig if they weren’t paid enough.

But this is where it all fell apart because, for the next 250 years, businessmen have done everything in their power to maximise their profits while minimising the wages and working conditions of their employees. Thus, it soon became apparent that Capitalism was a very, very bad deal for the workers. They had become trapped inside a game of chess in which they were merely the pawns.

“In essence, the Capitalists had turned what Adam Smith had needed one thousand pages to explain into one short sentence: Greed is Good. It’s the Gordon Gekko line from the 1987 movie Wall Street.Gekko conveniently Tipp-Ex’d out the bit in the Wealth of Nations where Adam Smith also insisted that the workers must be protected from monopolies.”

Feeling rather chuffed that he’d condensed Capitalism into two paragraphs, the Director paused to see how all this was going down with his young student. George, meanwhile, was puzzling over what Tipp-Ex might be.

“Adam Smith could no more have foreseen the impact of his treatise than Henry Ford could be blamed for the phenomenon of Jeremy Clarkson, yet here we are.

“In fact, I’d like to think that Adam Smith would have been so aghast by how things turned out that, like Alec Guinness in The Bridge Over The River Kwai, he’d havesaid the immortal words, What have I done? and blown the whole fucking monstrosity up.

2.5: This Charming Man

George noticed how excited his new mentor was when discussing these obscure historical figures, so it seemed appropriate to walk beside this old river with its Victorian warehouses and factories on either side now, of course, all converted into expensive apartments.

“But I’m willing to cut Adam Smith some slack,” continued the Director in a more magnanimous tone. “We’ve got to remember that Smith was scribbling away with a quill pen when he wrote The Wealth of Nations. The Industrial Revolution hadn’t yet begun to bite, and he couldn’t possibly know that, in a mere 40 years, William Blake would be looking out over dark Satanic Mills?

“It’s incredible how quickly the world changed once the avarice of Capitalism kicked in.

“You see, Adam Smith’s theories and conclusions couldn’t help but be shaped and influenced by his limited world-view that were the accepted realities of the time. Slavery was still acceptable, and the East India Company’s private army was at the peak of its power, busily subjugating whole continents in the name of British trade. This was all perfectly normal behaviour for the Britain of Adam Smith, even if he largely disagreed with it.”

George, ever eager to contribute, chimed in. “I get that. Sometimes, you can’t believe you once thought something was OK when it clearly wasn’t. It’s like when I used to think Kanye West was an amazing artist. Now, when I look back, I wonder, ‘How the hell could I have listened to an asshole like that?’

“Exactly!” responded the Director, pleased that George was still listening while trying not to be too disturbed by the crass analogy.

“Don’t get me wrong, Smith was way ahead of his time regarding human rights. It’s ironic to think he’d probably be considered woke by the Adam Smith Institute, which now abuses the great man’s name to promote its own right-wing agenda.

“Back then, the Earth seemed boundless. The world’s population was only 800 million, and vast tracts of land were yet to be discovered. So, even Smith, though a prominent figure of The Enlightenment, was undeniably a product of his age, and it would be unfair to expect him to foresee how his cherished Capitalist ideas would cause such human and environmental destruction.

“But I can’t let Smith off the hook entirely. He was, after all, criminally naive if he thought the unscrupulous GRiFTers wouldn’t distort his ideas and use them to ride roughshod over the planet.

“As he said himself: Despite being selfish and wanting to gratify their own vain and insatiable desires, the rich are led by an invisible hand which makes nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life that would have been made had the earth been divided equally among all its inhabitants.

“Which, in hindsight, is just stupid. People are inherently greedy, and Smith was giving them permission to be as greedy as they could possibly get away with. And, as the Industrial Revolution unfolded, it was clear this unbridled greed gave hem permission to be unutterably horrible to other human beings. To the GRiFTers, the working class were just another resource to be exploited and, if needs be, destroyed alongside the natural world and all the species within it.

“Nor could Smith have known what this would mean for the planet. As early as 1896, a Swedish chemist called Svante Arrhenius predicted that

soaring levels of CO2 in the atmosphere would create global warming, but, of course, no one was in the mood to listen; not when there was money to be made.

2.6. You’re As Cold As Ice

“It’s easy to assume Adam Smith was uncovering some universal law that applied everywhere in all circumstances to all people, but this was one of the problems with the Enlightenment thinkers.

“During the Age of Reason, scientists assumed that everything could be understood through what they called the Scientific Method as opposed to just making shit up, which is pretty much what had happened before then. Isaac Newton used the Scientific Method todeduce the existence of gravity, which, along with a bunch of other scientific breakthroughs, led to the belief that there was some sort of secret mathematical code that would unlock the mysteries of the universe and everything in it. A bit like the instructions you get with an IKEA flatpack. But all that fell apart when Einstein came along with his out-of-the-box thinking. Comparing Newton to Einstein would be like comparing a cassette tape with Spotify. So let’s hear it for Einstein!”

“Yeah! Go, Einstein!” cheered George with muted enthusiasm.

“And, just like Newton was wrong when he assumed the universe was some sort of mechanical clock, Adam Smith was equally wrong when he suggested The Wealth of Nations contained some kind of universal truth about selfish man. It was nothing of the sort. It was just a snapshot of 18th Century Europe. Not that you’d know it from the way economists still fawn over his every word all these years later — at least the bits they want to agree with. The world has evolved since then, and the way humans relate to each other has evolved too, yet Adam Smith’s central idea — that people work best together when they behave selfishly — still drives modern economics and political thinking as though it’s an incontrovertible fact of life.”

“So we’ve ended up falling in line behind an idea that isn’t necessarily true?” Asked George quizzically.

“Yup.” Replied the Director tersely. “We used to think the Earth was flat, and we’d fall off the edge. But then, someone brave enough tested the theory and found it was actually round. It was just superstitious horseshit, and the idea that only Capitalism can save the world is horseshit too.”

“Jesus, when you put it like that, it does sound crazy!” Said George, nonplussed. Next to him was a short, portly Scotsman chattering ten to the dozen, and here he was, plodding along a poorly lit towpath, wondering how much further they’d have to walk before he could order a steak.

George furtively looked at the half-million dollar Richard Mille skeleton watch on his wrist to check the time. It felt about eleven, but he wasn’t sure. Maybe it just seemed like they’d been walking for a couple of hours. But it was dark, so he couldn’t see the silly little hands on the diamond encrusted watch face.

“You’re right. It really is crazy,” replied the Director, bringing George back into the present. “And there’s been many times when we’ve collectively asked ourselves whether Capitalism is the right way to go. But, like the turd you just can’t flush, it just keeps floating back.”

This made George chuckle.

2.7: Capitalist Growing Pains – 1800 – 1900

“But Capitalism hasn’t had the smooth ride you might expect from such a supposedly superior system. It certainly doesn’t live up to the brochure we’re given at school. There’s been many a time when the GRiFTers have allowed their lust for Status, Power & Money (S.P.A.M) to get the better of them, and each time they do, their whole rotten scam falls apart. And, just as predictably, it’s ordinary working folk who end up picking up the tab. I’m not exaggerating, George. Look it up if you don’t believe me.”

“I believe you!” Replied George defensively, not knowing whether to believe this grumpy senior citizen.

“And each time it happens, there’s a lot of hand wringing and talk of reform, but somehow those slippery little GRiFTers always find a way to persuade us to trust them, and the sorry cycle starts all over again.”

“You have to admit it sounds absurd.” Pushed back George more gently. “Are you absolutely sure this is what happens? I mean, aren’t we smarter than this? Aren’t we supposed to learn from our mistakes?”

“That’s a charming question.” Replied the Director, smiling ironically. “And a reasonable question too, but you’d be laughed at if you asked such a thing in professional circles. In my experience, whenever I talk to the money men”. (The Director used visual quotation marks to show his disdain for ‘money men‘), “The rules we follow in the real world somehow don’t seem to apply to them. I’ve a theory as to why that is, but first, let me offer some evidence to back up my claims.”

“Sure, fill your boots.” Said George. It was a phrase he’d heard his British friends use, though he had no idea what it meant.

So the Director began again. “Before I start — and in the spirit of full disclosure — there are plenty of examples of financial crashes that brought chaos to society before Adam Smith came on the scene. There was Tulip Mania in 1636 and the South Sea Bubble in 1720, both caused by mass hysteria at the thought of people missing out on a financial killing. Adam Smith and his capitalist theories certainly didn’t invent financial crashes, but since then, capitalists have certainly made up for lost time.

“The first big financial crash of American Capitalism was the Panic of 1819, triggered by a collapse in land prices. Twenty years later, they were hit by the Panic of 1837, again brought about by wild financial speculation in land and railways triggered by the Great Westward Expansion.

“And who could forget the Panic of 1857 and the Panic of 1873, both caused by bubbles in the American real estate market, the latter of which kicked off The Long Depression and two decades of crippling unemployment and poverty all across America. And finally, to tie up the loose ends of the 19th Century, let’s give a big hand to the Panic of ’93.”

“Whoo Hoo!” Said George in mock celebration.

“Notice anything, George?” Asked the Director.

“That there was a lot of people panicking?” Replied George ruefully.

“You’re absolutely right!” Agreed the Director. “Those masters of the universe are oh so macho when they’re making money on their investments, but as soon as there’s a chance they might lose some of their hoarded stash, they hit the panic button and soil themselves, leaving the rest of us to clean up the mess. The most recent big crash in 2008 resulted in fifteen years of austerity when essential public services were cut to pay off their debts. And not one of the bankers or traders carried the can. They never do. They’re like drunk drivers careering down a hill, getting more and more extreme in their speculation and risk-taking until they predictably hit a tree, get out of the wreckage, dust themselves down, and walk away without looking back. They might then lie low for a while, making plans, promising to make us all rich if we give them our money, and, once again, we’re stupid enough to fall for it. But I’m pretty sure if these financial wizards were as good at their job as they claim to be, they wouldn’t panic so much.”

“Maybe they need therapy?” Offered George, “A 12-step program perhaps?”

“You might just be right.” Agreed the Director, smiling. “It’s a glitch built into the Capitalist system and it certainly isn’t going away. I mean, before the ‘Panic of 1873,’ the French diplomat de Tocqueville was touring America making a few observations for his government.”

Suddenly, in a moment of mock drama, the Director stopped in his tracks, grabbed George by the arm, looked up to the stars, and proclaimed in a melodramatic French accent:

“Their desire for wealth is universal, ceaseless, and eternal. There are always individuals whose aspirations outstrip their possessions, willing to relinquish the serenity of ownership in pursuit of the pleasures of acquisition.”

“Even in 1832, de Tocqueville could see something was deeply wrong with a society built on Status, Power & Money (S.P.A.M).

“And after the crash of ’73, Mark Twain wrote The Gilded Age, which satirised America’s tasteless nouveau riche and the corrupt politicians who took money from the industrialists. After that, the whole period became known as The Gilded Age because American society looked like it was made of gold but, beneath the surface, it was just shit.”

“Perhaps if he’d written it today, he’d have called it The Polished Turd?” offered George in all seriousness.

“Maybe so.” Agreed the Director, chuckling at George’s ability to see through the superficial and get through to the heart of an issue. “And the fact that Capitalism is built on selfishness and greed sets a terrible precedent for how we treat each other as a society, made doubly destructive by the way greed and selfishness contaminate not just our day-to-day lives but our futures too. “

“How so?” Asked George. “Are Capitalists time travellers now?”

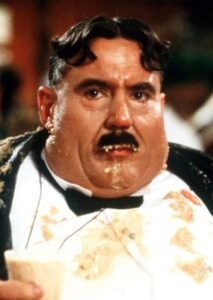

“Well, yes, in a way, they are.” Replied the Director, intrigued by this idea. “You see, the Capitalist Dragon isn’t satisfied with the simple profits it might make today; after all, there’s only so much a dragon can eat in twenty-four hours. But imagine how much more it can devour if it lines up those meals for the next hundred years! That’s where the real profits are; that, and the thought of how much food it can pile up tomorrow and the next day and ad infinitum, really gets it smacking its lips.”

“That really is a little disgusting.” Said George, genuinely feeling a little nauseous as he imagined that bloated and obese creature. “That’s the very definition of greed.” He added.

“You’re right; it IS disgusting.” Agreed the Director, adding, “Just one more wafer-thin mint!” in a ridiculous French accent.

“de Tocqueville?” Asked George, a little confused.

“Mr. Creosote.” Corrected the Director casually, wishing he hadn’t said it, and swiftly moving on. “And this insatiable need to hoard as much as they can, be it food or wealth, that destroys a society. They call it Speculation.“

“Well, You’ve got to Speculate to Accumulate.” Chimed in George, recalling something his dad used to say. “But judging from what it’s done to the planet, make that When you Speculate, you Devastate.”

“You’re dead right.” Nodded the Director, appreciating the point. “And given that stockbrokers tend to throw themselves from 15-storey windows whenever there’s a crash, you could say They Speculate ’til they Defenestrate. Ho ho ho.”

The Director looked to see if George had got the joke — but all he could see in George’s face was metaphorical tumbleweeds.

“Whatever…” said the Director after a moment of awkward silence. “Speculation is surely a terrible way to run a society. I mean, the clue’s in the name: Speculation literally means ‘Reasoning based on inconclusive evidence; conjecture or supposition.’ It’s basically just a fancy name for gambling, and it is the cause of every single financial crash we’ve ever had, from the South Sea Bubble and Tulip Fever to the Subprime Crash of 2008. Yet the bankers make out what they’re doing is some sort of complicated science we mortal folks couldn’t possibly understand. And it’s important for them to keep up that myth; how would it seem if we finally realised that, when you boil it all down, it’s just gambling, pure and simple.”

“Sound like a bad weekend in Vegas.” Reflected George.

“Except they’re playing with our money, and when they lose their shirts and are thrown out of the casino, ordinary folk have to bail them out. And given how much they’re paid, the fancy cars they drive, the big houses they live in, and the sense of entitled superiority they radiate, you’d think they’d be pretty good at what they do, wouldn’t you?”

“You’d think.” agreed George, shrugging, already preparing himself to be contradicted.

“Yep, well, you’d be wrong because, in 2013, the Observer newspaper conducted an experiment which confirmed what a lot of us already suspected that, despite all the hype, these Masters of the Universe are no better at speculating than the rest of us.”

“How so?” Asked George, intrigued.

“Well, the newspaper challenged a team of top stockbrokers to pick £5,000 worth of any stocks they thought would yield a good return on their investments. Meanwhile, a cat called Orlando selected stocks by throwing a toy mouse at a list of FTSE 100 companies. After three months, each ‘team’ swapped out any stock that wasn’t performing, and, at the end of the year, the profits for each ‘team’ were calculated, and it turns out Orlando outperformed the stockbrokers by 4.2%. And it was no fluke. Yet, despite all this, we still look up to these Capitalists, assuming they are some sort of genius race when, in true to free-market conventions, they are only out to enrich themselves and have zero interest in our wellbeing. It’s just bizarre!”

2.8: The New Deal, Bretton Woods & Attlee’s Welfare State

George and the Director were now walking past the windows of the lovely old pubs near Hammersmith Bridge. George looked in to see a welcoming bar full of happy drinkers, and he wondered whether he could persuade the Director to drop in for a last pint themselves. His feet were hurting, and so was his head, and for a moment, he thought he might suggest they leave off this critique of Capitalism and pick it up again the next time he was in town.

But as he looked at the Director and the urgency he needed to explain his ideas, George realised the least he could do was listen. After all, wasn’t this the problem the Director had warned him about — apathy and hubris? Could something as urgent as a climate disaster be put off until another day? And in any case, the Director was clearly in no mood to stop, so even suggesting such a thing would seem pointless.

The History of Capitalism would surely be the Director’s specialist subject if he ever appeared on Celebrity Mastermind.

”We’re now entering the 20th Century, George and the Wall Street Crash of 1927 and the Great Depression.” Said the Director with enthusiastic relish.

George comforted himself with the idea that things were getting more up-to-date, and he might be able to relate to it more.

“The fallout from the Great Depression was so terrible that Roosevelt felt he had no choice but to make the most drastic social intervention in the 150-year history of Capitalism. Roosevelt called it the New Deal.

“This New Deal created millions of jobs, rebuilt America’s crumbling infrastructure and drastically overhauled the financial sector, separating commercial banking from investment banking to prevent the unregulated speculation that had been the cause of financial crashes of the past.

“Other European countries followed suit, with Germany in particular taking the opportunity to rebuild its armies and autobahns, amongst other things.

“Roosevelt’s New Deal did a lot of socialist things that Americans had always shied away from. Things like old-age pensions, unemployment payments, and welfare benefits. It built vast numbers of roads, bridges, social housing, and lots of cultural projects which employed artists. It also promoted nature and expanded the national parks. In fact, it created much of what America is today and put the country on a much stronger footing in the run-up to the Second World War.”

“I remember all this from school,” agreed George, happy to hear about something he was vaguely familiar with.

“Yet, predictably, the GRiFTers downplayed the benefits of the New Deal, claiming it was a socialist plot and government intrusion into people’s lives. Surprise, surprise, they also said it limited their ability to make money.

“By 1944, Germany was losing the war, but with the world now a smoking ruin, it was clear that Capitalism wouldn’t be able to get it back on its feet. For Capitalism to work, you need buyers and sellers, but all the buyers were either dead or destitute, and Capitalism, therefore, had nothing to offer.”

“Funny how there’s never a GRiFTer around when you need one.” Quipped George.”

The Director chuckled before continuing: “So Roosevelt and Churchill sent their chief economists to Bretton Woods in New Hampshire, where they devised a new monetary system to jolt the world back to life.

“Bretton Woods is mainly remembered for John Maynard Keynes setting up the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction, which became the World Bank, and most importantly, tied international currencies to the US Dollar, which created financial stability and promoted cooperation between countries. Obviously, the GRiFTers hated it.”

“Obviously”, confirmed George solemnly.

“The last example of governments trying to contain the excesses of Capitalism I want to describe was the Clement Attlee Post-War Welfare State. Ever heard about that, George?” asked the Director optimistically.

“No, can’t say I have.” Replied George. “History was never my thing.”

“Well, have you heard of the National Health Service, you know, the NHS?” Asked the Director in an equally optimistic tone, like a proud grandparent introducing his grandson to a friend.

“Yes, now that I have!” Replied George, hoping it was what he thought it was. “They talk about it in the States a lot. It’s a waste of money, and the service is terrible.”

“Yes, that’s the one!” Replied the Director, chuckling. “They hate it over there. They think it’s a communist plot to undercut Big Pharma.”

“Probably something like that”, confirmed George.

“Well, don’t be fooled, George. The NHS is a beautiful thing. Free healthcare for everyone. And the GRiFTers have been trying to take it away from us ever since. We voted for a socialist government after the war, which more or less applied the ideas that John Maynard Keynes had suggested at Bretton Woods; such as government intervention, a welfare state, and nationalising industries like coal, steel, and railways. All paid for through taxing the rich.

“And, like Roosevelt’s New Deal, Attlee’s policies were really successful, and also like the New Deal, the GRiFTers hated it. How could the Capitalists make money if all these industries were publicly owned?

“Maybe these successful government interventions had finally tamed Capitalism? After all, by taking away the opportunity to speculate and create debts, the world was more stable, and the chance of a global recession was significantly reduced.”

“You’d think so.” Agreed George.

“Not so fast…” Cautioned the Director.

2.9. The Dragon Unchained

“The world emerged from two world wars a safer place thanks to some enlightened thinking.” Continued the Director. “What could possibly go wrong?”

“I’m not sure,” replied George, “but I’ve a horrible feeling I’m about to find out.”

“You’re right, George, it wasn’t good. In fact, what’s happened since the 1970s has been absolutely terrible. OK, if I tell you about it?”

“Why not?” replied George, sounding somewhat resigned. “We’ve come this far. There’s no turning back now.”

“That’s the spirit”, replied the Director, laughing enthusiastically and slapping George on the back. “Just a couple more things to tell you about, and we’ll have reached your hotel, and we can get something to eat.”

George found this a very comforting thought.

“So,” began the Director again, preparing for a lengthy discourse. “Thanks to Bretton Woods, things went pretty well for America after the war. The dollar was now the world’s currency, and America was the most prosperous country on the planet.

“But this wasn’t enough for Tricky Richard Nixon. According to the rules set up at Bretton Woods, the US was obliged to keep as much gold in Fort

Knox as there were dollars in circulation, and this was simply impossible given he had a war with Vietnam to finance and a nuclear arms race with Russia to win. He needed more money, and he needed to borrow it, but this was against the rules. So, in 1971, with little consideration for the consequences, he unilaterally canned the Bretton Woods initiative. This event was later called The Nixon Shock.

“Nixon could now spend as much as his little heart and imperialist foreign policies desired. However, it also meant that currency exchange rates were directly determined by market forces, opening the door to speculators. Capitalism was once again unleashed. We’re talking about free trade, floating exchange rates, unregulated debt; the lot. All the things that had caused financial crashes in the past.

“And just like The Great Panic, the Long Depression and the Wall Street Crash, it didn’t take long for laissez-faire economics to screw things up again.

“Nixon had concluded that Bretton Woods was holding him back after listening to a group of right-wing thinkers called The Chicago School, led by an economist named Milton Friedman.

“Friedman wasn’t a fan of government meddling and had devised a theory he called Trickle-Down, which was, more or less, a rehash of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand.

“Friedman believed the free market was the best way to generate wealth, which might be true, but just as in the case of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand, this wealth tends to miraculously pool at the top where the Elite play and remarkably little of it trickles down to where the poor work.”

“I’ve seen this movie before.” Noted George drily.

“You’re right,” agreed the Director. “Free-market economists love to run their cost-benefit analysis spreadsheets over projects like this. The ‘benefit’ column includes innovation, investment, efficiency, and maybe even higher living standards and life expectancy. But, when it comes to adding up the ‘cost’ column, they downplay factors like inequality, pollution and even catastrophic environmental disasters. And I don’t care how they try to spin it, but increased life expectancy isn’t much of a benefit IF THE PLANET KILLS US FIRST! So thanks a lot, Milton Friedman, but you can take your free-market, laissez-faire, trickle-down economics and stick it where the sun don’t shine.”

Coming from California, George hadn’t heard this expression before, and it didn’t make a lot of sense because in Tinsel Town, the sun pretty much shone everywhere all of the time.

“By the 1980s, Reagan and Thatcher had jumped on the Friedman bandwagon and were rabidly tearing up regulations, left, right and centre; deregulating the banks and the stock market, abolishing fixed commission charges, privatising industries and tearing down social safety nets and generally trashing anything that looked like The New Deal or the Welfare State.

“The Thatcher Government were so pleased with itself that they even gave their social vandalism a name: The Big Bang. And, in doing so, they blew the bloody doors off and invited a hoard of short-term profiteers to come in and ransack the British economy.

“I doubt she thought too hard about it at the time, but perhaps the most significant contribution Thatcher made to the crisis we’re dealing with today was her encouragement of the City of London to take the brakes off electronic trading. In 1980, computers were just being introduced into the trading markets, making the dangers of speculating ten times worse.”

“Sounds scary”, remarked George, pretending to shiver with fear.

“You might be terrified in a minute when I tell you what happens next. The Big Bang did indeed encourage growth and lower inflation for a while, but gradually, greed crept back into the system, and, predictably, the gap between the rich and poor grew wider again. Hey – and guess what? In ’87, we had Black Wednesday; in ’99, we had the Dot-Com Bubble; and, in 2008, we were hit with the mother of all crashes: the Subprime Mortgage Crisis, which brought down the entire world banking system. Who could have possibly seen that coming?”

“Beats me!” Joshed George, in mock confusion. “Maybe the same greedy bastards that screwed things up the last time?”

“Got it in one,” confirmed the Director, “but what was different this time was the effect this new technology would have on the world of finance. I’m not sure how well Friedman and his genius Chicago chums understood the ramifications of effectively unleashing a Dragon on steroids. Still, I’m guessing even if they had foreseen it, they’d have considered it a good thing. But like so much else in their simplistic, amoral, black-and-white world, they’d have been spectacularly wrong.”

“Explain.” Requested George, needing more information before he understood this point.

“Well, thanks to the internet, the GRiFTers could now trade instantly with each other, cutting out the ‘middlemen’ of real people living in the real world. Reagan and Thatcher had created the perfect conditions where a whole new level of free-market Capitalism could thrive, where ordinary people became even more like counters in the game of global Monopoly, the GRiFTers were playing, ultimately bringing about the climate disaster we’ve been left to dealing with.”

“You’re right; that really does sound scary,” said George.

“Well, stay tuned because we aren’t finished with this shit yet.” Replied the Director grimly.