8.1. Cloudbusting

“So that’s more or less all I have to tell you,” said the Director. “I’ve reminded you just how dangerous the climate crisis is; I’ve explained that we must stop being complacent and change our behaviour is we want to avoid environmental armageddon. I’ve also identified the source of these problems: namely a social system that places profits over human well-being. I’ve provided the context that describes what Capitalism is, where it came from, and why it’s no longer fit for purpose.”

George nodded while all of this was being recapped.

“I then went on to discuss how there are alternatives to Capitalism and why we’ve got to start exploring them before it’s too late. And finally, I tried to make you understand why we can’t wait for someone else to take the initiative. We’ve all got to become hummingbirds ourselves. So, that’s it! My work here is done. Now, off you go!…” The Director gave a little bow, feeling a little lightheaded with relief.

“That’s fantastic, Sir, and thank you so much for spending your time explaining it all to me.” Responded George, who, despite feeling physically and mentally exhausted, was, nonetheless, genuinely appreciative of what the Director had done for him.

“I agree,” said Faye, who, despite being a paid-up socialist and already politically active, had to admit she’d been challenged to think of these problems from a somewhat different angle. However, she had one last request: “Before you go, can I first tell you that I love your movies, but secondly, can you give me some ideas about what I should do next. I mean, what can I do when I go to college tomorrow? What can I do to start being a hummingbird? It all seems just such an enormous task.”

The Director had sympathy with this sentiment, so while he sincerely wanted to finish his drink, help George to the elevator and head home to his wife, he instead said the following:

“I understand what you’re saying, Faye, I really do, so here’s the deal. Call me a cab for about 30 minutes from now — not an Uber, of course, because they’re a classic, exploitative GRiFTer organisation — but a local cab company — and in return, I’ll suggest what you can do tomorrow that will start to change the world.”

“It’s a deal,” said Faye, taking the napkin the Director had written his address on and reaching for her phone. Meanwhile, George was finding it hard to keep his eyes open on the comfy bar stool beside him. This might have been the cue to turn in for the night and return to the subject another day. Instead, however, the Director was hit by a new burst of energy, like a marathon runner entering the stadium for the final stretch of the race.

“So, if you still think we can’t kill a dragon as big and powerful as Capitalism, let me tell you it’s been done many times before. In fact, progress only ever happens when an evil dragon is put to the sword.”

“Like Copernicus and his BIG IDEA ?” asked George, suddenly jolted into life and rubbing his face in an effort to wake himself up.

“Yes, just like Copernicus.” Agreed the Director.

“Copernicus, the Dragon Slayer – that’s got a ring to it,” agreed Faye, thinking it sounded like something from Game of Thrones.

“Dragons as big as Capitalism have been killed before, and they’ll be killed again. If you apply enough pressure to their throat, you eventually choke them to death.”

“Examples?” Asked Faye, cradling her chin in her hands in expectation.

“Well, I’ve got three good case studies where a small but determined group took on the Establishment and won emancipation. Want to hear about them?” He asked.

“What’s emancipation? Asked George. “Is it like constipation?”

“Actually, in a way, it is.” Chuckled the Director. “I mean, in all three of my examples, there’s a few hard-to-move shits blocking progress. But, to be more precise, emancipation simply means setting people free. In other words: Liberation.”

George made a rather droopy ‘OK’ sign with his fingers to show he understood.

“Take the Transatlantic Slave Trade.” Offered the Director. “That stain on the British conscience persisted for 200 years and made a lot of Capitalists very, very wealthy. Yet, in the end, it was killed off by a small group of determined activists who were so disgusted that they wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

“Interesting.” Agreed George, thinking this sounded more like a story he could follow. “Tell us more.”

Accepting this invitation, the Director gathered his thoughts, took a deep breath, and began. “OK. The Transatlantic Slave Trade started in the early years of the 16th Century. Over the next 200 years, around 17 million Africans were transported to North and South America and the Caribbean. In addition, millions more were killed during their capture, and 2 million died in transit.”

“Fuck.” Said George. Faye nodded in agreement.

“The British didn’t start the slave trade, but boy, did they cash in once they realised how much money could be made from capturing humans and shipping them off to the other side of the world. In the end, Britain was responsible for around half of the slaves transported, which, in turn, accounted for about 10% of the entire British economy at the time. Think about that if you ever wonder what lengths Capitalism allows men to go to in pursuit of a profit.”

Both George and Faye shook their heads in disgust.

“Gradually, thanks to the work of a small group of Hummingbirds known as Abolitionists (here the Director nodded in the direction of George in acknowledgement of his earlier contribution), it became too difficult to ignore this obscenity and the practice was formally ended with the passing of the Abolition of the Slavery Act of 1807. The United States followed suit the next year.

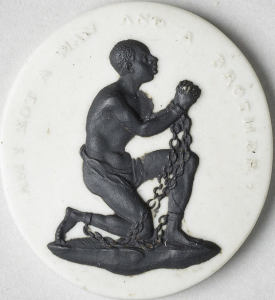

The Abolitionists famouslyincluded William Wilberforce and Josiah Wedgwood, who were affiliated with the Quaker movement and, therefore, motivated by more than just making money. Part of Wedgwood’s contribution was to create a ceramic medallion of an African in chains inscribed with the slogan Am I not a man and a brother? Which supporters hung around their necks, a lot like we wear Just Stop Oil t-shirts these days. (Here’s an image of the medallion for viewers at home)

“And I bet the Establishment back then were just as dismissive of Wilberforce and Wedgwood as they are about the Just Stop Oil activists today.” Suggested Faye.

“I’m sure you’re right”, agreed the Director. “And even then, the slave ships kept operating illegally for another 60 years, which shows you just how hard it is to force Capitalists to let go of something when it’s making them money. But the interesting thing I want you to note here is something called the Overton Window.”

“Ah yes, I wrote an essay about this last term.” Commented Faye approvingly.

“What’s this then?” Asked George, feeling he might be thrown out of that window if he didn’t stay awake.

“Well,” explained the Director, “The Overton Window is a sort of snapshot of public sentiment at any one point in time. The Slave Trade, for example, was considered acceptable when it first began in the 1600s. Still, by the early 1900s, thanks to people like Wilberforce and Wedgwood, the idea of trading human lives had become unpalatable. Moving the Overton Window to such an extent that British politicians had no choice but to act. And that’s how change comes about. You move the Overton Window by educating and informing. What at the outset seems impossible becomes reality if enough people apply enough pressure and move the window, and that’s how we can abolish Capitalism too.”

The Director was encouraged to see George and Faye giving this some thought, so he pressed on.

“So let’s think of a different example of something which seemed impossible to change before it was finally consigned to the dustbin of Capitalist shittiness.”

“OK” Agreed George, wanting to hear more.

“Let’s look at how ordinary folk in Britain finally won the right to vote.”

“Classic Example!” Agreed Faye, settling down for a good listen.

“Three hundred years ago, the British Establishment considered the working class too irresponsible, and, frankly, too stupid, to be consulted about how their lives should be lived. But, of course, there was another reason: The people with all the power and money didn’t want to give any of it away to a bunch of oiks they considered an almost lower life form.”

“Just how our Dragon saw Alice and George!” observed George.

“You’re catching on!” smiled the Director.

“It took over a century of protests before the landed gentry finally agreed to give up some of their power.”

“There’s plenty of toffs out there who still haven’t come to terms with this,” added Faye ruefully.

“Too true,” agreed the Director. “It’s crazy to think it was only 200 years ago when only wealthy men had a say in how the country was run. What’s more, because they were wealthy, most had very little interest in the poor, whom they regarded simply as resources from which to make profits.”

“So what’s new?” asked Faye.

“In 1819, working conditions had become so bad in the industrialised cities of the North that 60,000 factory workers demonstrated to ask for better treatment and political reform. The Establishment were more than a little concerned, as they’d seen something similar happening in France thirty years earlier when a lot of wealthy heads ended up in baskets. So, rather than take that risk, the army was called in, and 18 demonstrators were killed, and over 700 were severely injured.”

“Peterloo…” Confirmed Faye, solemnly shaking her head.

“That’s the one.” Nodded the Director. “Which put the working class back in their box for a while.”

“Bastards.” Muttered George quietly to himself.

“Then, after a pause of about 20 years, in which working conditions got even worse, a grassroots movement called the Chartists sprang up. It didn’t have leaders or a manifesto, so, in that respect, it was a great example of Spontaneous Order, yet it managed to organise a nationwide petition of several million signatures, which it delivered to Parliament.”

“Wow – good on them!” said George appreciatively. “Again, just like Alice and George.”

“That’s right, and, just like Alice and George, they were completely ignored.” Said the Director. “So they organised a second one and then another. And they were all ignored.”

“Bastards.” Repeated George.

“So eventually, the movement fizzled out due to lack of progress.”

“Shame.” Said George, genuinely saddened.

“Nonetheless,” continued the Director, now in full lecture mode. “In 1867, voting rights were extended fractionally to include men renting property for £10 or more a year.”

“Gee – big deal.” Said George. “And Women?”

Faye, who knew this story well, shook her head.

“So next, at the turn of the Twentieth Century, came the Suffragettes,” continued the Director, as if he’d just seen the cavalry riding over the hill. “They were led by women like Emmeline Pankhurst who were not about to put up with any shit. The Suffragettes vandalised public buildings, went on hunger strike and threw themselves under racehorses. In fact, they made a royal nuisance of themselves.”

“Like Extinction Rebellion activists do today.” Noted George.

“That’s right! And after another 20 years of civil disobedience, their efforts finally paid off: In 1918, men AND women who’d fought in the Great War were allowed to vote and, in 1928, ALL men and women were finally included.”

“Jeez, it’s like pulling teeth!” Said George, unimpressed with the effort required to get The Establishment to change anything. “It reminds me of watching those penny-falls machines in amusement arcades.” He reflected dreamily.

“Quite so”, agreed the Director. “It took a long time, but eventually, the pennies dropped.

“To be fair, if we must,” added Faye reluctantly, knowing something about this subject. “For a Victorian, democracy would have seemed an alien concept. After all, the most recent example they’d have been able to refer to was that of Ancient Greece, three thousand years earlier!”

“You’re right!” Agreed the Director magnanimously, “It’s easy to forget what a novelty democracy would have seemed back then. And, in a way, that’s exactly the situation our politicians now find themselves in. They have no idea what a post-capitalist system might look like, as there are no obvious examples to compare it with. And, of course, the GRiFTers would much prefer it if we didn’t bother thinking about it at all. Which is why we are trying to open up the debate with our Dragon movie.”

“History’s a wonderful thing.” Observed George reflecting on what he’d learned in the last ten minutes.

“But only if we really do learn from it.” Warned Faye. “Otherwise, we’ll keep repeating it.”

“And, as I’ve already said, it’ll be written by the victors.” Concluded the Director, with a hint of finality, “Only, this time, there won’t be any victors.”

George lowered his head and made a sad, groaning noise.

“But while we’re on the subject of history, there’s one more example of a dragon slaying I’d like to tell you about.”

“Go on,” said George, unsure whether he could handle any more information but felt too enervated to resist.

“OK, I will, but I want to tell you about this because the strategy they used might be something we can learn from.”

“Sounds helpful.” Agreed Faye, a little more intrigued and much less drunk than George.

“I’m talking about Gandhi’s strategy for evicting the British from India.”

“Oooh! Now THIS is something I AM interested in!” proclaimed George, suddenly energised. “Ben Kingsley!”

The Director rolled his eyes but pressed on.

“So here was a particularly brutal dragon: The British had controlled India’s 425 million population by force for almost 200 years, so it must have been hard for an Indian to imagine ever having enough power to kick them out. After all, Britain, at the time, was the most powerful empire the world had ever seen.”

“A quarter of the globe coloured pink.” Added Faye for extra detail.

“Indeed,” agreed the Director, “and they were brutal bastards who showed no mercy when they needed to suppress the locals.”

“In the end though, Gandhi proved that if you inspire enough people to commit non-violent acts of disobedience, even the most powerful dragons can be sent packing.”

“Go Gandhi!” Said George with all the enthusiasm he could still muster.

“What’s great about this is that Gandhi achieved emancipation without bloodshed. He knew the British were vicious when it came to suppressing violent uprisings, and he also knew they would have no idea how to deal with a strategy of passive-aggressive non-cooperation. After all, there are only so many innocent people you can murder before the tide of opinion turns against you.”

“The Overton Window.” Noted Faye.

“That’s right.” Agreed the Director. “So Gandhi and his followers slowly strangled the enemy to death like a python killing a goat.”

“Nice,” agreed George appreciatively, vaguely thinking about eating a goat curry on his flight back to LA.”

“First, he refused to pay tax on salt.” Continued the Director.

“Again with the Salt?” asked George, sounding a lot like Woody Allen.

“Yep, Salt!” Confirmed the Director. “The British taxed the Indians for using salt. SALT, for god’s sake! Gandhi said, ‘Enough of this bullshit’ and walked 200 miles to the Indian Ocean, where he made his own salt, thank you very much. In 1930, Mahatma Gandhi set off on his Salt March with 80 supporters. Still, by the time he’d reached the sea, he was leading a massive crowd, 60,000 of whom were then arrested. Gandhi went to prison for two years, but this only made his followers more determined.

Next, hundreds of thousands of Indian civil servants put down their pens and refused to work, causing the infrastructure of the whole Raj to grind to a halt. And then, in an act that very much mirrors the sort of consumer boycotts I’m suggesting we use to stop climate change, the Indians stopped buying imported British goods, and this really hit them where it hurts.”

“So the yen is mightier than the sword!” exclaimed George joyfully.

“They use rupees in India.” Corrected Faye.

“Never let details get in the way of a good pun.” Consoled the Director, patting his tipsy leading man on the back. “But, yes, money is the quickest way to make a capitalist change his mind, if that’s what you mean. And there’s a beautiful irony here: the British had been shipping Indian cotton to Northern England and Scotland for over a century and then selling it back to the Indians as paisley saris and pyjamas. The Indians were literally a captive market. So when this cosy arrangement abruptly dried up, it left a gaping hole in Britain’s balance of trade. Gandhi called this strategy Satyagraha, which literally means ‘truth force’, which I think is great because that’s precisely what it was: the force of a people driven by truth, which, in this case, was the truth that Britain had no right to force itself upon the people of India.

And ‘Truth Force’ is exactly how we’ll stop Capitalism from killing the planet. Once we see the truth of what’s happening, we’ll find the collective will to find a better way.

We can learn a lot more from Gandhi’s strategy of Satyagraha, but I think we might all be asleep if I talked about it for much longer.”

“Not at all.” Mumbled George, trying to keep his eyes open.

8.2. I Can See Clearly Now

Conscious that at least 50% of his audience might soon drop off, the Director knew he needed to inject some energy into the conversation.

“And if you think that these examples were all a long time ago and far away and that nothing much changes, then let me tell you, this couldn’t be further from the truth.”

“Like what? Give me some examples,” challenged Faye, keen to hear something more up-to-date to inspire her.

“OK,” agreed the Director, picking up her gauntlet. “Who’d have thought the world could have ground to a halt in 2020 when Covid hit? Governments didn’t know what to do until, eventually, the global capitalist system was put on hold, and people were paid to stay at home. Crazy, right? Even now, it’s hard to believe this happened. It’s a brief moment in time when we catch a glimpse of the underlying weakness of selfish Capitalism and, conversely, the power of a society that decides to look after each other. Capitalism failed us, but the sky didn’t fall in. And when it was all over, we went back to work as if nothing had happened.

“Many capitalist countries had to implement massive social programs to keep people and businesses alive, walking away from their right-wing principles of laissez-faire economics. It was a stunning example of how we mindlessly comply with Capitalism’s false assertions.

“Moreover, it allowed many of us to step back from the daily grind and rethink our priorities. There was a sharp rise in early retirement and the economically inactive, which is just a technical term for dropping out like a 1960s hippie.

“And just like the financial crash of 2008, when governments were forced to bail out the banks through Quantitative Easing (just another name for printing money), the myth of Capitalism was laid bare, leaving the politicians, economists, financiers and CEOs looking exactly like the Wizard of Oz, pulling fake levers and wheels while telling us not to look behind the curtain.”

“Exactly!” Said Faye in complete and profound agreement.

“And the fall-out from those crazy times has been interesting. Some companies have adopted a four-day work week, arguing it has increased productivity, employee satisfaction, and the work-life balance. The average workweek in the Netherlands is now around 29 hours. Yet, the Netherlands is more productive per person than either the UK or the US. So, things can change quickly if we let them, and things will need to change much quicker than they have in the past if we want to stay alive.

We will have to look deeper into what we value in life and what motivates us.” Insisted the Director, with something of an evangelical look in his pale, blue and now rather sleepy eyes. “We’ve got to see that this irrational urge to fulfil our selfish needs must now give way to a more powerful desire for mutual cooperation. When enough of us see beyond Capitalism’s constraints, we can change the world.”

“Hear, Hear!” Said Faye.

“Well, said.” Agreed George, clapping a little.

“If you want still more up-to-date examples of humanity triumphing over Capitalism, maybe read Rutger Bregman’s book Humankind: A Hopeful History, which challenges the assumption that our species is inherently selfish and violent.

There are hundreds of books on the subject when you start looking for them. When you’re on your plane tomorrow, George, fire up your iPad and look up Doughnut Economics or alternative terms such as Post-growth, Sustainable degrowth, Economic contraction, Voluntary simplicity, Prosperity without growth, Anti-consumerism or Post-consumerism. Then maybe look closer at the alternative economics section of your local bookstore that will have books about Regenerative Economics, Circular Economics, Sustainable Economics, Holistic Economics, Thriving Earth Economics, Ecocentric Economics, Resilient Economics, Well-being Economics, or Equitable Economics.

The Director gasped in air as though he’d just named all 52 states of America in one breath.

“Then there are dozens, if not hundreds, of groups, organisations, and local chapters looking to spread the word. Once you become engaged with the subject, you’ll be amazed at how much is happening. I’m pretty sure the organisers of these groups would love it if a famous person such as yourself got involved.”

George nodded and tried to look engaged.

“Bregman also wrote a book in 2016 called Utopia for Realists, which discusses specific policies such as Universal Basic Income, Open Borders, and a 15-hour Workweek. All of which becomes possible once we look beyond the false assumptions Capitalism throws up to protect itself.”

“What I wouldn’t do for a 15-hour workweek” Mused Faye. “Imagine what else I could achieve if I wasn’t standing here for 40 hours a week!”

“You’re right.” Agreed the Director. “Bregman wants us to be audacious in our aspirations. We only live once and ought to demand a more sustainable and kinder world in which to spend it. But it’s hard, isn’t it? We’re so programmed to think that ideas like this are silly fantasies that could never work, but that’s exactly what the GRiFTers want you to think. Yet these ideas may not be quite so crazy if we tried them.”

Both Faye and George nodded solemnly.

“Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast, said the White Queen.” Smiled Faye.

“Quite so!” Agreed the Director. “And, in fact, an increasing number of thinkers, politicians and economists agree with Bregman. But you’ve probably never heard of them.”

“Could that be because of the hegemony?” asked George sarcastically.

“The Hegemony.” Confirmed the Director.

“We find it hard to think outside the box, so we just don’t bother: It’s too much like hard work.

At this moment, something snapped in Faye’s head. She’d decided she’d heard enough and that it was time to speak up and support the Director’s ideas. “Back in the day, I bet thousands of would-be hummingbirds hated the Slave Trade but did nothing about it because it seemed too powerful to stop. The same’s true of the would-be hummingbirds who believed every adult in Britain should have a vote, but they stayed silent for the same reason. Fortunately, there were still enough hummingbirds willing to try to change things, even if they couldn’t be sure they’d achieve their objectives. Because of their actions, they shifted the Overton Window and changed how the world works.”

“So very true.” Agreed the Director, proud of what he’d just heard. “Hopefully, we’ll all soon begin to see that, just like the slave trade, Capitalism is really not a good way for a civilised and intelligent society to behave.”

8.3. Do You Realise…?

“OK, OK, OK!” Slurred George. “You’ve both convinced me. I’m a hummingbird ready to join a Satyagraha, or whatever that Gandhi thing was called. Sign me up! What do you want me to do now? What’s the post-capitalist equivalent of melting down my pots and pans or going on a Salt March?”

“George, I’m not going to give you a shopping list”, replied the Director in a calming tone. “I’m just delighted that I’ve lit a fire under you. That makes me happier than you can possibly imagine.”

“And it makes me happy that you’re happy.’ Added George sleepily, now patting the front of the Directors chest with his big floppy hand.

“I won’t start handing out edicts or ask you to slavishly follow a programme. There’s no manifesto from me. Although Marx wrote a manifesto, he didn’t think a classless society would happen if we simply joined a big club and started following orders. Lenin and Trotsky tried that, and it didn’t work out well for them.”

“Marx didn’t want to be part of a club that would have him as a member.” Quipped Faye, pleased with herself.

“Very good!” acknowledged the Director. “But I guess that’s exactly what he meant. He knew you couldn’t have a successful revolution if it was imposed from the top down. In his mind, it needed to be organic. Just like the strategy Gandhi used: Mass disobedience, withdrawal of labour and a refusal to buy the products that fed the Capitalist economy. And that’s exactly what we need to do, too. Marx advocated a withdrawal of labour. I’m advocating a withdrawal of consumption. When consumers stop consuming, Capitalism will run out of the fuel it needs to survive. Its demise won’t come from the beheading of its GRiFTer ringleaders but from seven billion tiny cuts from the beaks of every human hummingbird on the planet.”

“Wow!” Gasped George, impressed by this dramatic image.

“If we stop tolerating the selfish, greedy behaviour that Capitalism demands, we’ll soon shift that Overton Window. For you, George, it might start by auctioning off a couple of your Porsches for a charity and turning over an acre of your Beverly Hills mansion to an allotment, and start growing your own vegetables. The single biggest impact we can all make to climate change is through our diets. We’ve all got to eat far less meat and fish and cut it out of our diet entirely if we can. Quite apart from the disgusting way we treat other defenceless, innocent species, especially through factory farming, our craving for meat is destroying habitat, including the rainforests and is a highly inefficient way to feed ourselves. As David Attenborough says, ‘the world simply cannot sustain billions of meat eaters’.

Given that George was still savouring the steak he’d only recently eaten, this was a challenging thought. Yet the Director’s words reminded him of something he often tried not to contemplate; that he knew he didn’t have the guts to kill an animal himself. That, to do so, would make him feel sick. So why was it OK to pay someone else to do the dirty work for him? On top of that, the Director was now telling him his food choices were helping to destroy the planet… Even in his drunken state, he knew this had to change.

“It definitely means telling your financial adviser to shift your investments out of dodgy pension funds and shares in GRiFTer companies and move them into initiatives that are 100% ethical and doing good in the world.”

George rubbed his chin as he contemplated these rather drastic actions.

“After that, maybe you should stop being sponsored by Richard Mille. I mean, who needs a half-million-dollar watch anyway?”

“I’ve got another one at home worth a million.” Corrected George sheepishly. “In my defence, it came with the job.”

The Director gave George his ‘slightly disappointed’ comical face. “Well, at least donate your fee to saving the rainforest or something and look at their business model, and if you find any dirt, maybe they use child labour to mine their diamonds or something, then publicly refuse to work for them. But in their defence, I think they’re a private company, so at least they’re not just another GRiFTer investment scam.”

George nodded in agreement. “Good to hear. I’ll look into them when I get home and maybe ask them some awkward questions.”

“Attaboy!” said the Director, encouragingly. “You’ll still be famous; you’ll just be more Jimmy Wales on Wikipedia than Mark Zuckerberg on Facebook. And I know who I’d prefer to have a beer with. After that, there are a bunch of alternatives to consumer capitalism. I’m not going to say which one is best. They all do a good job and work together. It’s horses for courses; just do what you feel comfortable with. The important thing is to do SOMETHING!”

“After that, you could start buying the things you need from cooperatives and worker-owned enterprises where employees have a stake in the business. And, is it true you part-own a soccer club in Wales?”

“You’re correct.” Confirmed George, pretending to head a football.

How about widening the club’s purpose beyond making a profit to include community-based initiatives, like getting kids off the street and setting up academies? God knows North Wales needs it.”

George nodded his head in agreement.

“Certainly, we must immediately stop buying from GRiFTers or working for their rotten corporations. To do that, we all need to be far more aware of how GRiFTers operate and the businesses they profit from. We could develop a kite mark or something legally forcing a business to explain who owns them and how they’re financed. That way, we could make better decisions about who we choose to support. These GRiFTer organisations are really just parasites, and we are their hosts, and their sole purpose in life is to siphon off our cash into their off-shore bank accounts, none of which helps to save the planet.”

“Sounds good.” Replied George, trying hard to hide his regret at the thought of saying goodbye to his beautiful Porsche.

“I can see you’re thinking about your cars, George.”

“No, no, not at all,” replied George, lying.

“But imagine a world where success isn’t measured by the car you drive, but how you feel inside, knowing things are getting better for everyone, not just the privileged few.”

George nodded in agreement and then quoted from his favourite book again: ‘Where you live,’ the little prince said, ‘people grow five thousand roses in one garden, … yet they don’t find what they are looking for.’

“Beautifully put.” Complimented the Director. “Imagine how you’d feel if you turned on your TV and saw good news stories about rainforests that had been preserved and animals that had been saved from extinction or better health services for poor African nations. What sort of price would you put on that?”

“A lot.” Agreed George, nodding again.

“What if Capitalism became so unacceptable that oligarchs and dictators were no longer allowed to hoard their stolen money in Swiss banks? Perhaps those failed states could rebuild and let their citizens feed and house themselves rather than depend on foreign aid.

“Imagine a world where innovation focused on sustainable solutions over oil spills, quality triumphed over quantity, and long-term well-being was more valuable than short-term financial gains. Imagine if we become as intolerant of greed and selfishness in public life as we are in our private lives. What sort of world would that be like to live in?”

“A pretty good one.” Conceded George.

“It’s all there waiting to happen if we can find the courage to evict the GRiFTers from the wheelhouse. Without them in charge, we could steer the ship into calmer waters where our pale blue dot would be loved and cherished. That’s what an intelligent species would do, and I believe we can do it. We just need to STOP BEING SO FUCKING STUPID!” The Director banged his fist on the bar as he shouted this.

“I don’t know about you, but I want to live in a world that celebrates the best of what humans can be rather than watching the worst of us on television every night.

“And escaping the grip of unchecked Capitalism doesn’t mean sacrificing our individuality. In fact, if we just wriggle out of this Capitalist straitjacket, we can realise our full potential as individuals. We can start to design a new system that better reflects who we are, more able to live our lives as we want them to be, untroubled by the environmental catastrophe hanging over us.

“Imagine if we were all self-actualised, George, and could explore our full potential and talents. How much greater would our lives be if we didn’t look for status from the watch we wear, the car we drive, or the weekly session with our shrink trying to straighten us out.”

“I know exactly what you’re talking about.” Confirmed George, realising the Director was now describing the three exciting years he’d spent at drama college when he felt everything was possible. “That was Lee Strasberg’s philosophy,” he said. “When I was at the Actors Studio in New York, we called it Flow. If you’re a method actor, you get to glimpse what a fully expressed life looks like when you really get inside a character.”

“Exactly!” Agreed the Director enthusiastically, though not sure George was what you’d call a method actor.

“The problem is, I’ve probably only been in a state of Flow five times my whole life. Those moments when I’ve been 100% present. And I haven’t felt that way for the past fifteen years.”

“Well, maybe it’s time to give it another shot.” Said the Director encouragingly. “This may be the moment you stop trying to be a film star and start being a human being again.”

“You’re probably right.” Agreed George, reflecting on his last few supposedly successful years.

“You see, George, we aren’t designed to be selfish. We’re deeply spiritual creatures striving to be the best we can be, sharing this incredible miracle of life with the fellow souls around us.

As Jeremy Honey said, It’s when we recognise the reality around us for what it is rather than what we expect it to be. Intimacy happens when we remove our preconceived ideas and allow our souls to be in the company of one another.

“That’s great”,’ said Faye, returning to the conversation, having spent a few minutes tidying up the bar and getting ready to close. “But who’s Jeremy Honey?”

“I’m not sure”, replied the Director, “But that’s not important now. What is important is that within the cul-de-sac of Capitalism, we’ve trapped ourselves; some of us have grown rich, many more of us remain poor, and almost all of us have lost sight of how to enjoy life. It’s caused wars, famine and vast amounts of suffering, and it’s destroying our planet. How can we continue to support that? Within this hall of distorting mirrors, it might seem pretentious or naive to aspire to anything as grand as a happy, healthy, caring world, but that’s just the hegemony talking. Capitalism has even taken away our ability to be optimistic.”

George and Faye just looked at each other, touched by the words tumbling from his mouth.

“If you think about it, just for a moment, you’d realise it’s a miracle the three of us are sitting in this garish bar at two-thirty in the morning. If we dollied the camera back, we’d see our pale blue dot floating in the infinite blackness, unsure where we’ve come from or where we’re going. It’s a magnificent mystery, and I’m damn sure I’m not going to waste whatever time I’ve got left indulging in something as crass as Capitalism.

George and Faye listened to this poetic vision intoned by this gnarled old Scotsman, his voice mellow as the glass of vintage malt he was holding.

“Aristotle was saying something similar two and a half thousand years ago.” Continued the Director. “He called it Eudaimonia, which was his way of describing a life of happiness and fulfilment. He knew a thing or two about the human condition and its unique capacity for rational thought mixed with the passions of the human soul. He believed we could all rise above the mundanity of the day-to-day and be present to the transcendent miracle of life.

“Most importantly, he argued that we can only achieve a state of Eudaimonia through meaningful relationships. Taoists and Buddhists believe something similar. So, if we’re going to consign Capitalism to the scrap heap and look for something better, let’s go the whole hog and see how far we can take it. Shoot for the moon; if we miss, we’ll still be amongst the stars.”

“Yeah, but then we’ll be floating in space, waiting for our oxygen to run out.” Replied George, staring into his now long-empty glass and somewhat deflating the moment.

8.4. Stand By Me

“Have you ever seen Pay it Forwards?” Faye asked George.

“Kevin Spacey?” said George slowly, now almost monosyllabic. “Not his best work.”

“That’s the one.” Confirmed Faye.

“Why do you ask? Enquired the Director, puzzled.

“Oh, I don’t know. Talking about that hummingbird made me think about it.” Replied Faye. “The hummingbird wasn’t trying to put out the fire for her own sake, but for all the animals in the jungle and all the little hummingbirds that would come after her.”

“More like Spray it Forwards, then.” Said George, remembering the water the little hummingbird carried in her beak.

“I know what you’re getting at,” agreed the Director, slowly beginning to see the link. “Tell me more about the film. I don’t think they showed it at my local arthouse.”

“OK, so from what I can remember, a class of kids are told to come up with an idea that will change the world.” Faye made rabbit ears to suggest that changing the world was some sort of cliche. “And this one kid suggests that if someone does you a favour, you don’t pay them back immediately, but you pay it forward to three new people who, in turn, do something kind for three more new people.”

“Interesting!” Agreed the Director, appreciating the appropriateness of this idea to their conversation.

“Thanks for making that connection.” He said to Faye. “This is actually a very old idea known as serial reciprocity.”

“Is there nothing you don’t know?” Asked George incredulously.

“Well, I don’t know much about Kevin Bacon films.” Replied the Director, smiling at George.

“Kevin Spacey.” Corrected George, now on the verge of zoning out completely.

“Benjamin Franklin asked a friend of his to do something similar while living in Paris. I’m paraphrasing, but he said something like:

If I lend you this money, promise me that, instead of paying me back, you’ll lend the same amount to someone in similar distress and then ask him to do the same. That way, it will help a lot of people before it reaches a knave that stops its progress. This is a trick of mine to do a deal of good with a little money.

“How the hell do you remember all this stuff?” asked George again, completely baffled.

“I’m not sure,” replied the Director. “I guess I just read a lot of Wikipedia pages. Fittingly, too, Pay it Forwards is one of the steps in the 12-Step

Programme that Alice and George present to the dragon in their ultimatum ‘You can’t pay anyone back for what has happened to you, so you try to find someone you can pay forward.’

“There have even been experiments looking at the Pay it Forward effect, which suggests that people who receive good deeds are more likely to do good deeds themselves. Even small things like being a courteous driver encourage other drivers to be courteous, too. It’s what they call a virtuous circle.”

“They obviously haven’t driven in LA.” Reflected George sardonically.

Ignoring this comment, Faye continued. “It sounds like Karma. You know, Hindus believe our past deeds influence our future.”

“You’re right,” the Director agreed. “I think we could use this for our Hummingbird campaign.”

“How do you mean?” asked Faye, not really sure she had followed the Director’s train of thought.

“Well, this reminds me of that old WW1 recruitment poster I was telling George about earlier.”

“Oh yeah!” replied George, vaguely remembering that earlier episode from this massive box set. “The one where the poor dad is morally shamed for being a coward!” (Here’s that poster again for the viewers at home)

“That’s the one!” Chuckled the Director. “But if you think about it, there’s a good idea here we might use to encourage people to do more to save the planet.”

“How do you mean?” asked George. “Are we into emotional blackmail and dad shaming now? Doesn’t sound very Eudaimonia.”

“You’re right.” Agreed the Director again, but what if we removed the blackmailing and virtue signalling and let people see it for what it is?”

“What’s that?” Asked Faye, still somewhat unsure.

“People supporting each other in the fight against global warming.” Replied the Director.

“Dig for Victory!” Shouted George, not exactly sure why.

“Imagine if we created an online site where people could keep a record of the things we are doing for the war effort? So when children ask their parents what they’d done in the ten crucial years between 2024 and 2034 when we still had a chance to prevent an environmental disaster, their parents could point to the Hummingbird Book and show them what they’d done.”

“Are you sure?” Asked Faye. “Are things really as bad as the First World War, which killed sixteen million people?”

“Peanuts.” Replied the Director dismissively. “The Climate War will kill all 8 billion of us if we don’t do something about it.”

Duly corrected and reminded of the gravity of the situation, Faye asked. “So you’d better tell me about this Hummingbird Book.”

“OK,” agreed the Director, “After the Great War, almost every town and village in Britain built a memorial to the people from that town who’d given their lives for their country. You still see them covered in poppies and wreaths every Remembrance Day.”

Faye nodded, appreciating the point being made.

“So why shouldn’t we acknowledge the sacrifices people are making in the war against climate change? Sure, you might think that’s over the top, but if there was somewhere people could go to record their experiences and share their ideas, such as how to cut down on our carbon footprint, or how to avoid GRiFTer companies or just stimulate conversation amongst the Eco-Worriers like you and me; that’s got to be a good thing. We’ve got to get this conversation out to a wider audience beyond just the Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion activists. We need this to go mainstream if we have any chance of saving ourselves.”

“So let’s create an online forum — something like Facebook but without Zuckerberg making money from it — and let’s call it the Hummingbird Book or something, where people can get inspired, find their own way to do their bit and feel less like they’re on their own.”

“This is beginning to sound like a plan!” Exclaimed Faye enthusiastically. “Maybe then people wouldn’t feel they were the only animal in the forest trying to put out the fire, even if it feels small; be part of a bigger movement – the satyagraha: Truth Force.”

“Good idea.” Mumbled George. “That way, next time I see my niece, I can show her my page on the website, and she’ll see that I’d sold my Porsche and at least know I was trying. She might even be proud of me.” At this, George pretended to weep into his hands. “Tell you what.” He continued, “I’m flying back to LA tomorrow, and I’ll give a few of my pals in Silicon Valley a call to see if they can magic something up.”

“That would be marvellous!” Agreed the Director appreciatively. “I’ll call you in a couple of days to see if you’ve got anywhere with it.”

Even in his present state, George knew the Director would 100% keep his word on this and that he’d accidentally conscripted himself into the war effort.

8.5. Across The Universe

“That’s very noble of you, George.” Said the Director. “Which reminds me, I read this thing on Twitter this morning.”

The Director once again pulled out his battered old phone and started to read the tweet he’d seen earlier:

“Have you ever thought that, in 100 years, like in 2123, we will all be buried with our relatives and friends? Strangers will live in our homes we fought so hard to build, and they will own everything we have today. All our possessions will be unknown, including the car we spent a fortune on, and will probably be scrap. Our descendants will hardly know who we were, nor will they remember us. How many of us know our grandfather’s father? After we die, we will be remembered for a few more years, then we are just a portrait on someone’s bookshelf, and a few years later, our history, photos and deeds disappear into history’s oblivion. We won’t even be memories. If we paused one day to analyse these questions, perhaps we would understand how ignorant and weak the dream to achieve it all was. If we could only think about this, our approach and thoughts would change; we would be different people. Always having more and no time for what’s really valuable in life. I’d change all this to live and enjoy the walks I’ve never taken, the hugs I didn’t give, the kisses for our children and our loved ones, the jokes we didn’t have time for. Those would certainly be the most beautiful moments to remember; afterwards, they would fill our lives with joy. And some of us waste it day after day with greed, selfishness and intolerance. Every minute of life is priceless and will never be repeated, so take time to enjoy, be grateful for, and celebrate your existence.”

“Man, that’s fucking heavy.” Said Faye, entirely giving up on any pretence of being a member of the hotel staff.

The Director looked up from his screen to see George fighting to keep his eyes open. He glanced at his watch; it was 3:30, and he suddenly thought about his wife. Given that it was the end of the shoot, she wouldn’t have expected him home tonight, so she’d have gone to bed early. But if she’d woken in the night, she’d have probably wondered where he was and hoped he was OK.

He also remembered he’d arranged to play squash with his assistant at noon, and there was no chance of that happening now. Unfortunately, there was also no chance of sending her a text in his present state, so he hoped she’d forgive him for standing her up.

However, it was time to let George go, as he had a flight to catch in the morning. But the Director had one last point to make.

“So, the last thing I want to leave you with is this…”

George and Faye leaned in one last time to hear this final gem. This may be the most essential piece of the jigsaw they’d listen to tonight.

“Look, you know I’m a sucker for an acronym.”

“I had noticed.” Said George sarcastically.

“Well, let me leave you with just one more before we all turn in.”

“OK.” Said Faye. Is it memorable?”

“It ought to be.” Replied the Director. “Technically, it’s a mnemonic, so it’s designed to help you remember something important. Could you pass me one of these napkins, please?”

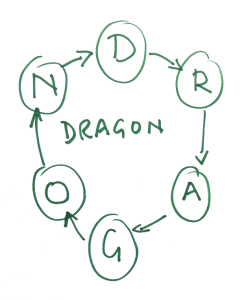

Faye did as requested while the Director felt behind his ear for his pencil. This is what he scribbled:

“Cool. What does it mean?” Asked George, swaying a little while squinting at the paper in the bar’s dim lights.

“D – R – A – G – O – N” confirmed the Director.

D – We need to wake up to the DANGER that’s looming over us

R – We need to take RESPONSIBILITY – because if we leave it to the Establishment, we’re all going to die.

A – We’ve got to learn to AVOID the GRiFTers because they’re zombie organisations that don’t care about our well-being.

G – We’ve got to practice being more GRATEFUL for what we already have — like our health, families and loved ones. And we’ve also got to resist being GREEDY. There’s enough to go around if we all just take what we need and nothing more. This leads to the idea of BUY LESS / BUY BETTER, but I couldn’t fit that into this mnemonic!

O – We need to learn to look out for each OTHER. We are all in this together.

N – Finally, we all need to take care of NATURE because if Nature dies, we die with it.

The Director now leaned in, his face very close to those of his friends, and jabbed his finger at them a little to emphasise the point as he now said very slowly and deliberately. “DON’T – FEED – THE – DRAGON. And remember this: the Dragon lives out there in the big, bad Capitalist world, but never forget it also lives here, in our greedy little hearts. So, whatever we do, we must remember it’s not enough to blame others. We’re as much a part of the problem as they are because we keep feeding them.”

And then, with an almost nonchalant smile, the Director drained the last tiny drop of whisky from his glass.

8.6. When Tomorrow Comes

“Come on, George,” said the Director, tapping George’s leg. “Let’s get you off to bed. I’ll walk you to the elevator.”

“Thank you so much,” replied George, genuinely grateful for the time the Director had devoted to him over the past nine hours, but now fast heading into oblivion. “I understand now, and I see things differently. Hopefully, when I wake up tomorrow, I’ll want to make some changes. It’s time to be more Hummingbird.”

“That’s great,” smiled the Director, again aware that George was just an innocent, eager puppy.

Faye and the Director shook hands in mutual recognition of a fellow traveller, their hands bridging their age difference and social standing. The Director fumbled in his battered old wallet for whatever notes were inside and left them on the bar before helping George from his stool. He also pushed the napkin he’d just been scribbling on and pushed it towards Faye, motioning that she should keep it.

George also waved a weary hand at Faye, then slid from his chair and was only prevented from slumping to the floor by the Director’s surprisingly muscular arm.

“I’ll make sure we get you to the premier.” Was the Director’s farewell line to Faye, shouted over his shoulder as he helped George to the door.

Faye shook her head, looked briefly at the napkin, smiled, and then returned to closing the bar. She never received a proper explanation for the Dragon and the role it played, but she guessed she’d find out if she ever saw the movie.

In the bright lobby, the Director guided George to the bank of gold elevators hidden off to the side. No one was around at this hour, so he pressed the elevator buttons himself to call one down. As they waited, the Director wondered whether the human species could get through this critical point in its history. Perhaps we had something in common with lemmings about to commit suicide, he speculated.

With this in mind, he pulled out his phone once more, only this time he held it away from his chin and spoke into it,” Siri, do lemmings really commit mass suicide?”

Siri instantly responded: “Lemmings are small rodents known for their periodic population fluctuations and migratory behaviour. Sometimes, during their migration, they accidentally fall from cliffs or into bodies of water, leading to the misconception of mass suicide. In reality, lemmings don’t intentionally take their lives.”

Relieved that this was just a myth, the Director returned his phone to his pocket and pressed the elevator button again, muttering about their slowness.

“So, no,” the Director continued out loud, aware he was now almost certainly speaking to himself. “It would be unnatural for a species like humans to kill themselves, but thanks to our hubris, we might do it anyway. But I’m counting on our Collective Unconscious and the miracle of Spontaneous Order to wake us up before that happens. This is one alarm we can’t afford to sleep through.”

George was no longer listening, leaning against the wall and focussing on not falling over.

“There’s just one last thing I want to reiterate,” persisted the Director, knowing that George was now probably too far gone, but saying it anyway, “The first and last thing we’ll need to save ourselves is TRUST.”

George pulled a face he hoped would suggest he understood.

“When you wake up tomorrow, George, and try to remember what we were talking about, you’ll have to TRUST yourself that what I’ve been saying today makes sense. You’ll need to TRUST yourself because, from now on, everything in this world will try to make you doubt it.”

George nodded excessively.

“And, what’s more,” continued the Director, “despite everything I’ve said about the human heart’s temptation to be selfish, you’re going to have to learn to TRUST everybody else too because, if we want any chance of building a new world out of the wreckage of this old one, we’re going to have to work together: So, our biggest enemy will be the fear that others will take advantage of us.”

Again, George nodded, hoping the elevator would arrive before he threw up on the carpet.

“So everything depends on our willingness to TRUST the process when all our instincts want to distrust it. We’d rather retreat under the duvet and avoid taking risks, but we can’t afford to do that if we want to live.”

Of course, retreating under a duvet was exactly what George wanted to do at that moment. Still, he could tell from the Director’s face this was important information he needed to hear.

Much to George’s relief, there was a bright ‘ping’, and the elevator doors quietly swooshed open.

“But that’s a conversation for another day!” Conceded the Director, finally acknowledging the moment had passed and throwing in the towel.

“By the way, George!” Said the Director as though he’d just realised something. “TRUST is the subject of my next film, and I was hoping you might consider taking the lead. Most of it will be filmed in Bhutan.”

George hadn’t entirely understood what the Director had said, but it sounded like a job offer. “Sounds great!” he replied, covering his bases. Get in touch with my agent, and let’s work something out.”

“Here you go, my young friend,” the Director said, guiding George into the empty elevator. “You did remarkably well today, George, and thank you for your thoughtful contributions.”

George patted the Director on the shoulder as he shuffled inside while the Director leaned in to press the floor corresponding with the number on George’s key card.

“Safe journey back. I’ll call you next week.”

The elevator doors closed, and George was left alone, vaguely wondering why the Director had persisted in calling him George all evening when his name was Brad.

As the Director gazed at his weary reflection in the closed elevator door, a spark of hope ignited, and he allowed himself a moment to believe thatthe ideas he’d shared would find a place in George’s heart. With this, he smiled to himself and stepped back into the lobby and out through the main doors into the cool, early morning air.

The sky was clear, with a hint of orange in the west, announcing either the pre-dawn or the lights of London’s Square Mile that never dimmed. He couldn’t figure out which. (It was the former, but he was too drunk to care.)

Looking up, the Director was struck by the vast expanse of the night sky, a tapestry of countless stars that sparkled like scattered diamond dust on a canvas of black velvet. In that moment, he couldn’t help but contemplate the potential tragedy of his generation being the last to witness this awe-inspiring sight. Just then, the cab, which had been patiently waiting for him, pulled up.

Grateful for his patience, the Director smiled at the turbaned driver, who smiled back serenely. He opened the car door, and climbed into the rear seat, confirmed his address and settled back for the short ride home. Just before closing his eyes, he noticed a small laminated card sellotaped to the driver’s dashboard, which he recognised as Taoist saying;

In the harmony of the universe,

Every action ripples through the whole.

The Director smiled at this, thanked the universe and then, in a blatant, ironic, post-modern twist, looked directly into the camera lens and said to you, the reader:

So, tell me, little Hummingbird, what are you going to do about it?

With that said, he rested his head back against the car seat as the car gently pulled away.

Thanks for reading!

Please add a short review or offer your own thoughts, observations or suggestions, and let me know what you think!

i’m not trying to feed you the answers, I’m merely looking to start a debate.