… “That’s a wrap!” Yelled the Director with a mixture of triumph and relief, ending the shooting for the day and the movie’s final scene. The previously silent ‘pub’ suddenly burst into life as ‘Alice’ and ‘George’ relaxed, set aside their prop glasses and shared a heartfelt hug across the table.

The sound engineer lowered the boom, the cameraman took her eye from the viewfinder, and the grip put down the reflective sheet she’d been using to light the actors’ faces. Four months of hard work had ended, and everyone was a little euphoric.

“Great job, everyone!” Continued the Director, clapping his hands while walking towards the actors. “I’m looking forward to having a drink tonight without that fucking dragon on my mind.”

Alice and George were used to the Director swearing. He did it a lot. “Absolutely!” exclaimed the actor who’d been playing Alice. “I won’t be thinking about the evils of capitalism for at least the next two weeks.”

“Why’s that?” asked the 40-something actor who’d been playing George, finally free from the difficult northern English accent he’d been wrestling with throughout the shoot.

“Well,” explained Alice, “I’m giving a speech at the Just Stop Oil rally in Trafalgar Square in the first week of November.”

“No rest for the woke-ed,” chuckled the Director, patting her on the back while anticipating he’d be in the crowd that night to hear her speak.

‘George’ felt a little left out of this conversation, his handsome, earnest face seen in so many leading roles in Hollywood blockbusters, but here playing against type.

He’d taken the male lead in this movie, quietly hoping for an Oscar or at least a BAFTA for his sympathetic portrayal of the conflicted middle manager. It was a unique blend of kitchen-sink drama and CGI-fest, and if it helped raise awareness of the climate crisis, all the better for the planet and his career.

White plastic cups were distributed, Prosecco was opened, and the extended crew gathered to celebrate the end of the shoot.

Half an hour and several bottles later, the crew returned to dismantle the set while the Director and his two leads continued to reflect on their completed work. They’d grappled with a complex script, which, together with the challenge of working with an imaginary dragon, had created some difficult moments. But now it was over, they sensed it was both a job well done and worth doing.

There was a lull in the conversation, and Alice saw this as a moment to check her watch. She’d promised her husband she’d be home by 7 o’clock to put her little ones to bed, and she’d been looking for a moment to respectfully say her goodbyes. This she did with a kiss on each cheek for George and a vast, friendly hug from the Director, with whom she was bound to work again soon.

George could see the Director was in a relaxed and approachable mood, so this was surely the moment he’d been waiting for to ask what had been on his mind since he’d first read the part. Until now, he’d avoided asking it for fear of looking superficial. Yet through all that subsequent time and even during the shoot, he hadn’t found an appropriate moment to ask the question. After all, the Director had a famously short temper and was well-known for directness, so George had no wish to get in his line of fire. And what if the gossip columnists had got hold of it? He could see the headlines now: ACTION HERO REALLY IS AS DUMB AS HE LOOKS. So, he’d kept his own counsel and hoped his acting would carry him through.

“So, how are you feeling? Are you satisfied with how it’s turned out?” he asked the Director tentatively, finally slipping out of character and returning to his easy Californian drawl. “Did you get what you wanted?”

The Director looked at George and warmly patted his shoulder. “Yes, I’m delighted, thank you. And you were outstanding.”

“Great!” George replied, his relief palpable. “I should have asked you this earlier, but what was it all about?”

Somewhat puzzled, the Director took a swig from his cup and asked. “What do you mean?” He had no idea the movie they’d just wrapped had gone entirely over George’s head.

George took a deep breath, realising he’d now have to own his ignorance. The Director was a short, stocky figure with a strong Scottish accent. George reckoned he must now be in his early 70s, and over his long career, he’d developed a reputation for being difficult, standing up to the studios for better pay for his technicians and marching in solidarity on the Iraq war, anti-Trump demos and, more recently, Gaza. So, little wonder George found him somewhat intimidating. Moreover, George and the Director had discussed the script every day for the past six weeks and met on set for a solid month to shoot it. So, for George to admit he hadn’t grasped the movie’s underlying message was frankly terrifying.

For a moment, the Director was unsure how to respond. Still, instead of anger, a depressing sense of defeat came over him. He’d always known that George wasn’t the sharpest tool in Hollywood, but it wasn’t George’s fault he hadn’t understood the message. Instead, the Director felt sympathy, realising that his failure to convey the story’s meaning to this actor, who’d been paid almost a million dollars to appear in the role, more accurately reflected his shortcomings as a storyteller.

“We’re doomed,” muttered the Director to himself as he gazed into George’s sincere, puppy-dog eyes. If he couldn’t convince George about climate change and motivate him to act on what he’d learned, how could he expect paying moviegoers to do the same? He wouldn’t blame the audience if they’d stood up and left the movie halfway through, marched back to the ticket office and asked for their money back.

The Director’s goal had always been to reach a mainstream audience caught between a rock and a hard place, the ‘rock’ being a growing awareness that the world is teetering on the brink of disaster and the ‘hard place’ of knowing that busy working people can’t just throw in their jobs and join Extinction Rebellion. He also believed the answers wouldn’t come from massive government interventions but rather from a billion individual commitments made by society as a whole. His mission, therefore, was to make every George in the world understand what they could do to help. So, the Director filled two large plastic cups with bubbly, mentally rolled up his sleeves, took a deep breath, and began to explain his story from the top.

“Take a seat,” he said, motioning George towards a canvas chair. “We have much to discuss.”

1.2: Comfortably Numb

“Okay, first things first,” began the Director with renewed resolve, “hand me that script over there on the table.”

George handed the Director the dog-eared, annotated script he’d been poring over between takes for the past four weeks.

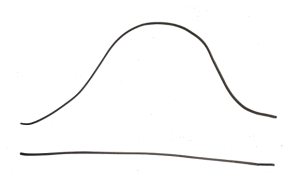

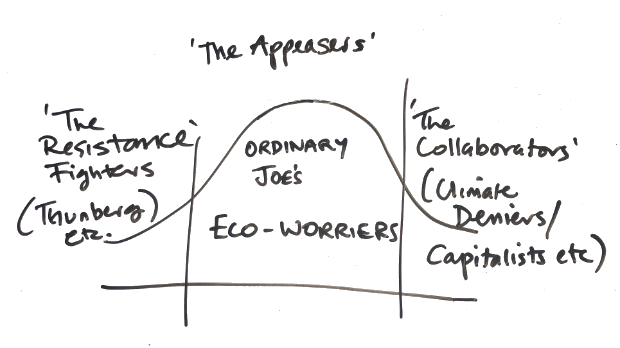

The Director retrieved a stubby pencil he habitually tucked behind his ear and began to draw a curve like this:

“Oh, Oh! I know what this is!” Exclaimed George, pleased with himself. “It’s a boa constrictor eating an elephant!”

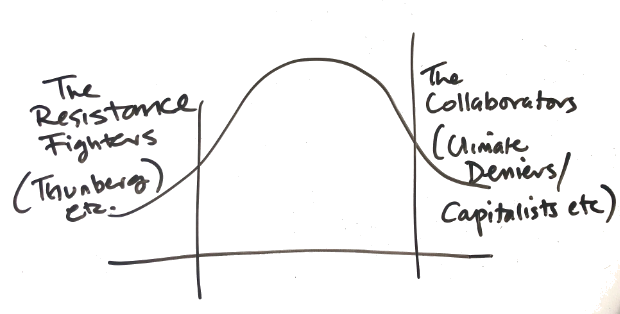

“What are you talking about?” asked the Director, somewhat bemused, “It’s a bell curve! I’m explaining who I was trying to reach when I wrote the screenplay,” before returning to his drawing with a look of concentration on his face.

“You see, at the moment, there’s a war going on between the small group of Eco-Warriors here on the left. People like Greta Thunberg and her Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion friends. They’re like freedom fighters in the battle against the CO2, which is causing Climate Change. Then, on the right here, we’ve got an equally small but much more powerful group of misguided climate-denying Capitalists who are more or less collaborating with an enemy that’s bent on destroying the planet.

“And then there’s a lot of ordinary folk in the middle here, who I’m calling the Eco-WORRIERS.” The Director made sure George understood this play on words. Then, pointing to the hump in the middle of the bell curve, he continued, “This lot, which probably includes you and me and most of the people we hang out with. You know, nice, middle-class people who can see something bad is happening but aren’t sure what to do about it. We can see a battle going on between the Resistance Fighters and the Collaborators, but at the moment, we’re still not sure whose side we’re on. So we just sit on the fence.”

“So climate change In-Activists then!” quipped George, “This reminds me of Star Wars, you know, the Rebel Alliance versus the Galactic Republic.” (George would find a popular movie to illustrate his point whenever possible.)

“You’re not far wrong,” smiled the Director approvingly. “But this isn’t ‘A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away’; this is right here on Earth, right now, and our planet is about to be destroyed by a Death Star, otherwise known as Climate Change!”

“Really?” Asked George, not sure if the Director was serious.

“And George, in case you’re wondering if I’m being serious,” responded the Director calmly, “I’m being deadly serious.”

The Director searched for a way to describe the urgency of the situation so that George could really grasp it. “You know that bit in Star Wars where Luke, Han, Leia and Chewy are being slowly crushed in the trash compactor?”

“Classic scene,” confirmed George, smiling as he recalled it. “Though I think you’re referring to Episode IV – A New Hope, Sir.”

“Whatever,” conceded the Director, “…the point I’m making is that’s where we are right now here on Earth. The walls are closing in, and this time, R2-D2 isn’t going to rescue us. This time, we’ll have to save ourselves or be crushed like cockroaches.”

This stark image wiped the smile off George’s face.

The Director continued his exposition, pleased to see he’d achieved his goal. “Sure, right now, we might take our reusable bags to the supermarket, try to cut down on our plastic bottle usage and look for the recyclable icon on the side of yoghurt pots. We might even make sure our coffee is Fairtrade, and our laundry detergent is environmentally friendly. And all of this helps us feel we’re doing our bit. Yet, despite all this, it’s hard to escape the uncomfortable feeling we ought to be doing something far more drastic. But when we think about that, it seems so complicated and inconvenient; we just keep our heads down and hope this nasty business quietly goes away. All of which makes us, more or less, Appeasers.“

George looked at the scribbles the Director was making while saying all this and mentally agreed he probably sat somewhere in the middle of that curve, just as the Director suggested.

“The thing is, you see”, continued the Director, “it’s us ECO-WORRIERS who make up 90 per cent of the population. People like teachers, doctors and nurses and honest, considerate folk working in shops and factories and people working from home. Older people and younger people. People who work for bosses, but also people who run their own businesses. They may even be the middle managers, like your character ‘George’ in the movie, who work for big corporations and drive electric cars. Most of the B-Corp brigade will be in there, too, and maybe even a few conflicted CEOs of multinationals, unsure how to get out of a job they no longer believe in.

“And I desperately want people to understand that if all of us here in the middle actually got our act together and mobilised, we’d have far more power than the rest of them combined. If only we knew it, all of us here in the middle have the power to stop this climate change crisis dead in its tracks; it’s just that we don’t know it yet. Collectively, we have the power to change everything, and I mean EVERYTHING.”

The Director waved his arms in a circle to emphasise this point.

“We can stop CO2 emissions if we really wanted to, but we don’t because, quite frankly, we’re too lazy, so we try not to think about it and wring our hands.

“Don’t get me wrong, I have the greatest respect for Greta Thunberg and her Extinction Rebellion heroes.” reassured the Director, “The Establishment hates her because they know she’s on to them and, if she has her way, she’ll stop them making money. And every time there’s an extreme weather event, like that time New York City turned orange or that inferno in Hawaii that killed so many people, we suspect she might be right. These are not isolated incidents, but signs of a rapidly changing climate that demands our attention.”

“We might even be prompted to look into what the Just Stop Oil people are so concerned about and why they’re willing to take the drastic action that will probably put them in jail. But it’s a little bit too uncomfortable to think about, so we turn on the telly, find a new Netflix boxset to binge on and hope it will all be sorted out by the time they get to the third season while reassuring ourselves that it’s probably not as bad as they’re making out. After all, we’re all still here, aren’t we?

“What’s more, who will employ us if we take part in Extinction Rebellion marches every weekend, having to call our boss on Monday morning to explain we’re in jail? Who’d feed our kids and pay the mortgage? So, it’s best not to think about it and let that sleeping dog snooze a bit longer.

“And we might also console ourselves that none of this could be as black and white as the Just Stop Oil fanatics make out. After all, plenty of intelligent, upstanding citizens are on the other side of the argument. Like the politicians and CEOs of multinational corporations who earn a ton of money and have important jobs, they must know what they’re talking about.

Not to mention the investment bankers and pension fund managers telling us not to worry about extremists like Greta, who, after all, are probably on the autistic spectrum anyway. And then, to seal the deal, they’ll remind us of how much we enjoy fast food, new cars and foreign holidays, all of which would be a thing of the past if we started to listen to the extremists. And every time Just Stop Oil blocks a road and prevents an ambulance from getting a critically ill patient to hospital, it’s an excellent opportunity to remind us that climate protesters are threatening our cherished way of life.”

“Whoa!” Said George, recoiling a little, “That escalated fast!”

“Hang on a minute, George,” replied the Director, not wanting to turn George off his thesis. “You might think this is a bit over-the-top, but the truth is, I’m only laying out the facts as they stand. Check them yourself if you don’t believe me. Maybe ten years ago, you could still find scientists willing to suggest that climate change was a myth but now it’s pretty much accepted as fact and we put climate deniers in the same category as Flat-Earthers. If there’s anything I’ve said that you disagree with, I’d love to hear it. You see, this isn’t a political issue: actually, the whole point of this movie was to demonstrate that climate change ISN’T about politics at all. Rather, it’s a personal issue for each of us as individuals. I’m not even trying to criticise the politicians or the Capitalists; that would be like blaming the rats for the black death. That’s too easy. Capitalists are just vectors. The people I’m really criticising in all of this are ourselves, who are turning a blind eye and hoping the problem will just go away. I blame our own complacency and wilful ignorance. The solution to climate change lies in the middle of this bell curve; when we come to terms with that, we might be able to begin to save ourselves.”

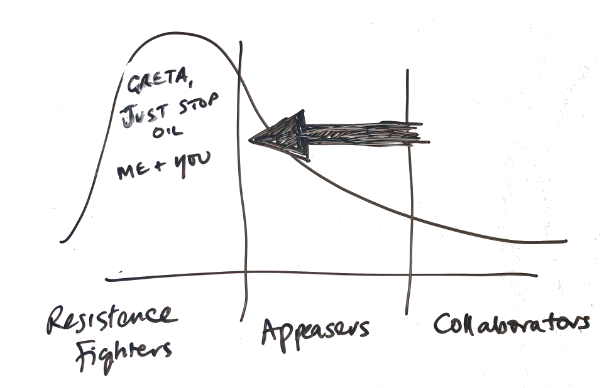

As he made these points, the Director continued to scribble away with his stubby pencil. “So what we’ve got to do, and the point of this movie”, he continued, “is to start shifting the narrative like this:” The Director drew a new curve to demonstrate to George his vision for escaping climate disaster. “When we move this curve, we’ll achieve critical mass, and when that happens, we’ll change our future.”

He now looked George in the eye and said earnestly, “The climate doesn’t discriminate. It’s a disaster that’s coming for all of us, so we’ve ALL got to do our bit to stop it. We’ve ALL got to stop appeasing and start resisting“.

“What’s more, what comes after might turn out to be so much better than what we have now… but I’m getting ahead of myself because nothing will be possible if we don’t stop burning fossil fuels.

“So, our first move in this war against CO2 is to halt the enemy’s advance and maybe even push it back a little. We need to buy some breathing space to give ourselves a chance to figure out what to do next, and we can’t wait. If we don’t do something quickly, all of this will be academic. BECAUSE WE’LL ALL BE DEAD!”

As you probably guessed, the Director shouted that last bit for emphasis, making George jump. Seeing this, the Director paused momentarily to collect his thoughts and give George a breather.

“As I said earlier,” he continued, more calmly now, “I happen to think that despite being unbelievably stupid, humans are also incredibly clever when we put our minds to it.

“When Kennedy said We choose to go to the Moon in 1962 he didn’t have the first clue how he would do it. But within eight years, Neil Armstrong was hopping around the lunar landscape, and Alan Shepard was hitting golf balls!

“People thought Kennedy was crazy to suggest such a thing, but they got behind his commitment anyway and the combined weight and willpower of the American scientific community lined up to deliver on his promise: It just shows what we can do when we pull our fingers out. Since then, we’ve managed to land a robot on an asteroid half a billion miles away, collect rocks from its surface and bring them back to Earth. So don’t tell me we can’t solve climate change. Compared to gathering asteroid dust, sorting out a dysfunctional economic system should be a piece of cake. But, unfortunately, there’s a hitch: the question is less about CAN we solve the problem and more, do we WANT to? Because, right now, our current system sees more profit in keeping things just the way they are.”

The Director finished his speech with a satisfied flourish, carefully laying the paper down in front of George and calmly pressing it flat.

“With me so far?” he asked.

“Yep,” replied George, relieved he’d come through this passage of the discussion without injury. “I’m a Resistance Fighter, ready to go to war. So where do I sign up?”

“That’s the spirit!” replied the Director. “Let me show you.”

1.3. – Apparently, We DID Start The Fire

“But before I do that,” said the Director, a little anti-climatically, “I want you to properly understand the problem because unless we have a clear idea of what we’re up against, we’ll only address the symptoms and not the cause. Does that make sense?”

“I guess so,” replied George, disappointed that he wouldn’t be getting a straightforward answer there and then, but nodding in agreement just the same.

The Director leaned in closer to George, his eyes alight with zeal. “Great, so first off, I’m going to explain why we’re so unwilling to get off our lazy backsides and do something about it.”

At this point, the Director sprang out of his chair and began walking around the studio, hands clasped behind his back, like a professor delivering a lecture to his undergraduates.

“Was it Schopenhauer or Plato who suggested that love was the defining characteristic of the human species?” asked the Director rhetorically.

George shrugged his shoulders; he hadn’t heard of either of them, but it didn’t sound much like something Pluto would say (after all, he was a dog), so he went for the Schopenhauer option.

“Never mind, it doesn’t matter,” replied the Director, fearing he might lose his audience if he didn’t dumb it down. “I think they both said it in one form or another, and, in my humble opinion, they were both wrong.

“Anyone who’s owned a dog has felt a dog’s love. So, no, love is not an emotion unique to humans. In fact, animals feel a purer form of love than most humans anyway, which, as far as I can tell, usually boils down to vanity, infatuation or insecurity. “Love isn’t unique to humans, but I’ll tell you what is: Hubris. Hubris is the thing that really sets us apart: we are the only species that thinks we’re superior to every other species… Come to think of it, the fact that we humans assume we’re the only species that feels love is a perfect example of our hubris. But I digress…

“I’m also sure we’re the only species that feels hate, but I’d contend that hubris is our defining and unique emotion. Hate will have us kill each other, but only hubris will have us kill ourselves.”

“That’s a great quote! Who said that?” asked curious George.

“I did!” replied the Director smugly. At this, the Director fell silent for a moment, as if for effect, and then continued dramatically, “But it was Dostoevsky who said:

‘Man, do not pride yourself on your superiority to the animals, for they are without sin, while you, with all your greatness, defile the earth and leave an ignoble trail behind you.’

“And I think it was Hubert Reeves who said: ‘Man is the most insane species. He worships an invisible god and destroys visible nature. Unaware that the nature he’s destroying is the god he worships’. And he was right about that, too”.

George was impressed that the Director could seemingly pull quotes from thin air and wondered if he practised them in front of the mirror.

“It wasn’t an iceberg that sank the Titanic, George, but the hubris of a bunch of Edwardian engineers who thought they’d built an unsinkable ship. It would seem the iceberg hadn’t got the memo.

“I first came across hubris when I was at RADA“, continued the Director, now dreamily reminiscing, “The Greeks loved it; so many plays where humans challenge their gods and get their asses kicked. ‘To those whom the Gods wish to destroy, they first make mad’, as Euripides put it.

This was Greek to George, too, but he decided not to interrupt the Director’s flow.

“We seem to have forgotten this. We don’t respect nature, George. We’ve been abusing her for the last 200 years, and she’s about to deliver some payback. We were even warned about it in the 70s when I first read Small is Beautiful. E. F. Schumacher told us all about it, and we all bought his book, but we ignored him and kept sleepwalking towards the cliff edge, just like we walked into war in 1939.

“In fact, it occurred to me the other day that the times we’re living through now are very similar to the 1930s when Hitler was making a nuisance of himself. He was looking for a fight, but instead of standing up to him, Britain and France chose to appease him, which he took as an invitation to rebuild the German army, occupy the Rhineland and invade Czechoslovakia.

We even looked the other way when he turned on the Jews, and all because we couldn’t face the idea of another war. Appeasement never works, but we’re doing it again. Only this time, our enemy isn’t a testicularly challenged dictator but an angry ecosystem looking for payback. And it will swat us like a fly if we don’t do something about it fast. And the crazy thing is, we’re already at war! Hawaii, California, Canada, and the Greek Islands have all been hit and if we don’t do something right now, it’ll soon be raining down fire on the rest of us.

“We ought to be throwing everything we have into a total war effort. Our leaders should be mobilising the whole of society, doing the equivalent of pulling up our iron railings and melting them down to build tanks and donating our pots and pans to be made into Spitfires. We should be Digging for Victory and joining the Home Guard. But instead, we sit on our arses, turn the TV channel on to something less worrying and hope the problem quietly goes away.

“We simply aren’t concerned enough. But if we’re too lazy or stupid to do it for ourselves, we should at least be doing it for our children and the magnificent planet we live on. It reminds me of that First World War recruitment poster on display at the Imperial War Museum in London called Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?” .

It was designed to make fathers feel guilty about not joining up — and we need something similar now. We need to shame people into taking climate change seriously because, in 50 years, their children and grandchildren will look at the state of the world and rightfully ask us, their parents, What did you do to try to stop it? That is, if we are still alive in 50 years, which given the direction the climate is heading in, we can’t take for granted.

Surely, if we’re decent human beings with a scintilla of compassion for the generations following us, we should do everything in our power to prevent the awful things that will be happening to them if we just do nothing. But what are we doing instead? We’re sitting in front of our televisions thinking about where we want to go on holiday.”

“I can’t even watch the television these days,” confessed George. “I used to love all those wildlife programmes, with that Brit guy, David Attenborough, up to his neck in bat dung.”

“Guano!” Exclaimed the Director, keen to correct him.

“Gesundheit,” replied George in all earnestness before continuing his anecdote, “but then, at the end of the show, Attenborough would tell us this or that species was now on the verge of extinction. It made me so sad I couldn’t watch them anymore.”

“That’s exactly what I’m talking about.” Agreed, the Director, touched by George’s sensitivity, “But I’m getting off the subject… What I wanted to say was that when it comes to the Climate War, Poland has already been overrun and it won’t be long before Britain has its Dunkirk moment all over again; by which time, it’ll all be too late. We’ll be under-prepared, out-gunned and on the verge of defeat. Congratulations, you assholes!”

The Director sat down with a thud, ‘Assholes’ left hanging in the air.

1.4: War: What Is It Good For?

After this apocalyptic outburst, the Director fell silent again, realising he’d become overwrought. He took a breath to calm himself down. George sat quietly, too, looking into his plastic cup, wondering what was coming next.

“I hate it when I get this upset,” said the Director, now more composed, “but when I think about what’s happening to our beautiful planet, I get so fucking angry.”

“You’re right to get angry,” said George, supportively.

“Well, George,” replied the Director, “if anyone ought to be angry, it’s you. As I’ve said, it was my generation of Boomers that caused this mess, and now we’ve just walked away, leaving you Gen X, Y and Zers to clean up the mess. If it’s not too late, that is.” The Director then began to fumble in his pocket, looking for his battered old phone with the cracked screen. “Take a look at this, and if this doesn’t scare the living crap out of you, nothing will”.

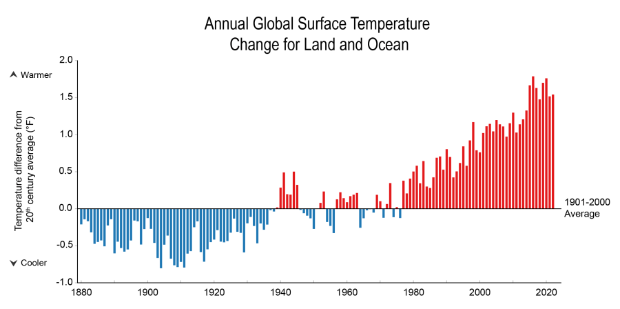

The Director offered George his phone. On the screen was a chart of average global temperatures from the last 100 years:

While George examined the chart, the Director explained the chart.

“Last year, the scientists looked at 34,000 climate studies – THIRTY-FOUR THOUSAND! — And concluded, as if we didn’t know already, that we are now suffering from intense heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, storms and floods and that much of this is irreversible. FUN FACT: The past 12 months were the hottest year in at least two million years. They also say the window of opportunity for action to prevent disaster is ‘brief and closing’. Brief and closing, reiterated the Director for effect.

“And the heat and the carbon dioxide aren’t the worst of it,” he continued in an increasingly resigned tone; the zombie apocalypse will have nothing on what’s coming. Before we die of heat exhaustion, there’s going to be societal breakdown. Water will be scarce, so we’ll fight each other for it. There’s going to be massive refugee displacement, which means a lot more boats coming over the English Channel and a lot more illegals climbing over Trump’s Wall”. The Director made it clear that he disapproved of the word illegal. “Agriculture will fail, food will be unaffordable, and energy will only be for the very rich who’ll guard it with their private militia.

“So here’s the irony: in this beautiful Capitalist world of the near future, which the politicians seem so keen to sell us, we won’t be buying new cars or going on exotic foreign holidays. No, no. We’ll be living in fear and scratching for food in the dirt. That, my friend, is the hubris I’m talking about. We’re like that ostrich with its head in the sand only it’s worse; not only is our head in the sand, but our ass is pointing to the sky, and there’s a firework sticking out of it, burning like a Roman Candle. Am I painting a picture of the mess we’ve created for ourselves?”

George nodded and slumped his shoulders, trying hard not to summon that particular image mind.

“And that’s why I made this movie. Because unless we all do as much as we can, not next year or next month, but RIGHT NOW, we’re all going to die a premature and unnecessary death.

“I know people will think I’m being extremist. They won’t want to listen to a crazy old man overreacting to something that will never happen, but that’s what they said in 1937. Right now, there are two big truths people are unwilling to confront.”

George Flt his obligation to ask “What are they?”, while simultaneously feeling unsure about whether he really wanted to know.

“Well, first,” replied the Director soberly, “we are facing an unavoidable crisis that will create chaos and anarchy. Second, Capitalism is the single cause of this crisis, and to prevent it, we will have to radically change how we live our lives.

“This is what we’re unwilling to confront because it seems so big and uncontrollable, while, at the same time, being unwilling to give up our dreams of buying a new car or a foreign holiday.

‘Jesus!’ was all George could think of to say as he quietly mulled over the Director’s analysis.

“And why are we going to let ourselves die?” Continued the Director, now on a roll. “Not because we don’t know what to do: we know why the climate is out of control, and we know what’s causing it, so why don’t we do something about it?”

Bewildered, George just shook his head.

“Because we’re asleep at the wheel, AND IT’S TIME WE WOKE UP!

There was another of those moments of silence as the Director composed himself again.

“And that’s the purpose of my film,” he said calmly. “It’s my attempt to wake us up. Woke isn’t just about Black Lives Matter or trans-gender rights; it’s literally about waking up to what we need to do to stop global warming.”

The Director then said in a slow and determined voice: “WE – NEED – TO – WAKE – THE – FUCK – UP!”

This certainly woke George up. He wasn’t sure where this conversation was going, and the shouting didn’t exactly help, but on the other hand he felt like he was being awoken from a drunker slumber by someone firmly shaking hi by the shoulder.

Unsure of what to say next, the two sat quietly, looking into the bottom of their empty plastic cups again.

After perhaps a minute, the Director decided to change the subject: “We’re like that frog they put in a pan of hot water.” He said reflectively.

“We’re eating frog’s legs now?” asked George, hoping to lighten the mood.

“Not exactly,” laughed the Director, “too garlicky for me; gives me heartburn. No, I was thinking more about why artists like us must use our imagination to make the world realise we’re being boiled alive. We need to wake them up before it’s too late.”

“I understand.” Said George, seeing now how he must support this passionate old filmmaking legend in his mission. “We’ve got to shake people awake. But what do we tell them once we’ve done that? We can tell them they’re in danger, but they’ll then need to know what they can do about it. This is the bit that’s missing for me. I now understand why you made the film and who you made it for, and you’ve explained how we’re just snoozing in front of the TV while our house is on fire. But what’s the alternative? What do you want me to do about it?”

The Director tried not to look surprised. This was the most coherent sentence he’d heard George utter in the past six months: a perfect summary of the Director’s theses to date. George had confronted the danger, agreed on its cause, embraced the urgency of the situation and now seemed willing to do something about it. The Director felt a flicker of optimism. Perhaps there was still hope…